By Jeanette Garretty, Chief Economist

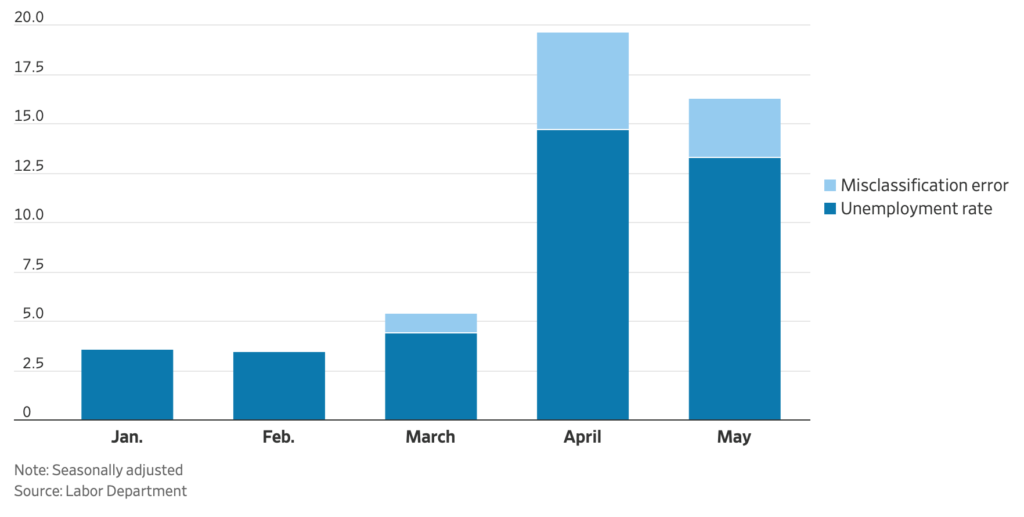

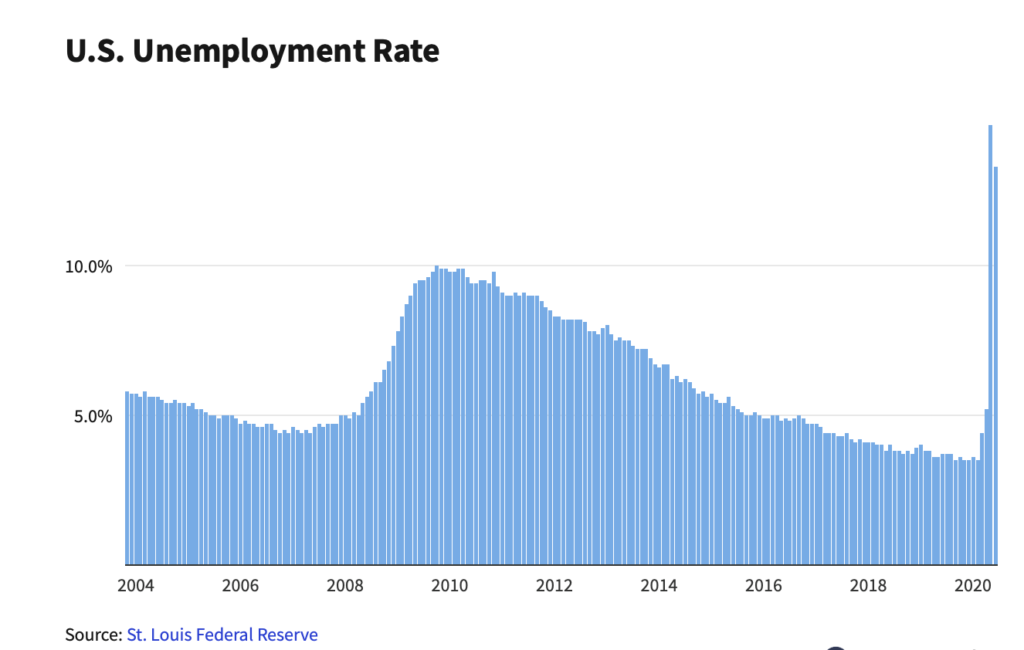

June 10, 2020 – The most recent report on US labor market conditions by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), released on June 5 and reporting on employment and unemployment in May 2020, has provoked a torrent of commentary on the accuracy of the survey data. In this particular case, the problem resides in the correct categorization of individuals who were “furloughed” or otherwise separated from their jobs for a (perceived) temporary period of time while the economy was shut down due to the coronavirus pandemic. The BLS has been aware since March that many individuals who should be correctly counted as unemployed were self-reporting themselves as “employed but absent”. Correcting for this error would have put the May unemployment rate at 16.3% instead of the reported 13.3% and the April unemployment rate at 19.7% instead of 14.7%.

Survey data is the bane of an economist’s life; an absolutely necessary tool for measuring many aspects of economic activity (after all, economics is a social science) but a frustration for a discipline that has pursued mathematical sophistication as the Holy Grail. Answers to surveys are highly sensitive to the phrasing of the question, the context in which the question is placed and the way in which a survey taker may explain the question if asked for clarification. Unfortunately, although economists are well-aware of the limits and liabilities of survey data, once the data is produced and disseminated these problems are often ignored or deliberately overlooked — sometimes even by economists themselves!

The unemployment rate should be a reminder of the appropriate way to utilize data, especially short-term data. First of all, the very fact that it is a rate — calculated as the number of people in the labor force who are not working as a percentage of the total labor force (people working and people actively looking for work) – introduces the opportunity for error/misclassification of two concepts, employment and labor force. Even if there are no errors, a rise in the unemployment rate can be a result of rising numbers of unemployed or falling labor force participation, and vice versa. Thus, it is always important to look at the actual numbers in the calculation. In May, the number of unemployed persons in the United States fell by 2.1 million; this, along with the downward direction of the unemployment rate (as the size of the labor force tends to hold constant in the short term) are the two most important observations, signaling the opening up of the US economy in May.

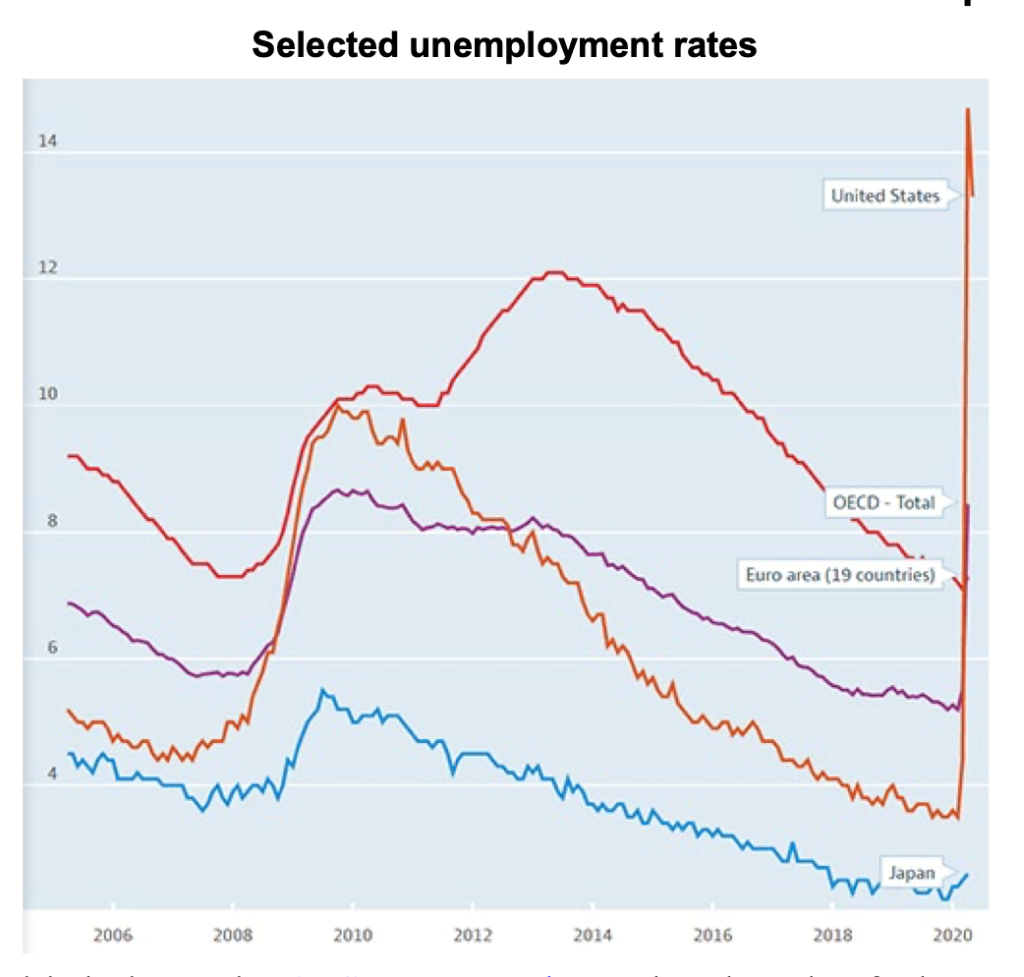

Survey data can become especially problematic when making comparative observations of global statistics that appear to be the same. Often times, the concept is the same but the data is dissimilar because of the survey method. Once again, unemployment provides a case in point.

On Tuesday, June 8, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) released unemployment rates for various countries, including the United States. Few of the countries report May data as yet, so the numbers reported are for April 2020. It is tempting to look at the chart and conclude that labor markets outside the United States have held up much better during the worst of the pandemic economic shutdowns.

Source: OECD

However, accompanying the June 8 OECD release was an important note:

The broad comparability of unemployment data across OECD countries is achieved through the adherence of national statistics to International Guidelines from the International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS) – the so-called ILO guidelines. Departures from these guidelines may however exist across countries depending on national circumstances (e.g. statistical environment, national regulations and practices). Typically, these departures have only a limited impact on broad comparability of employment and unemployment statistics. However, the unprecedented impact of COVID-19 is amplifying divergences and affects the cross-country comparability of unemployment statistics in this news release. This concerns in particular the treatment of persons on temporary layoff or employees furloughed by their employers. These are persons not at work during the survey reference week due to economic reasons and business conditions (i.e. lack of work, shortage of demand for goods and services, business closures or business moves).

According to ILO guidelines, ‘employed’ persons include those who, in their present job, were ‘not at work’ for a short duration but maintained a job attachment during their absence (ILO, 2013 and 2020). Job attachment is determined on the basis of the continued receipt of remuneration, and/or the total duration of the absence. In practice, formal or continued job attachment is established when :

1)the expected total duration of the absence is up to three months (which can be more than three months, if the return to employment in the same economic unit is guaranteed and, in the case of the pandemic, once the restrictions in place – where applicable – are lifted) OR

2)workers continue to receive remuneration from their employer ,including partial pay, even it they also receive support from other sources, including government schemes.

In turn persons are classified as ‘not employed’ if:

1)The expected total duration of absence is greater than three months or there is no or unknown expected return to the same economic unit AND

2)People in this condition do not receive any part of their remuneration from their employer.

Pity the poor analyst trying to figure out exactly what is being surveyed and categorized in any of these countries, but, rather amazingly, it would seem that the very thing the BLS is calling an “error” –furloughed workers who should be more properly counted as unemployed, not employed –is in fact consistent with the ILO guidelines referenced above!

And just to further complicate matters . . .

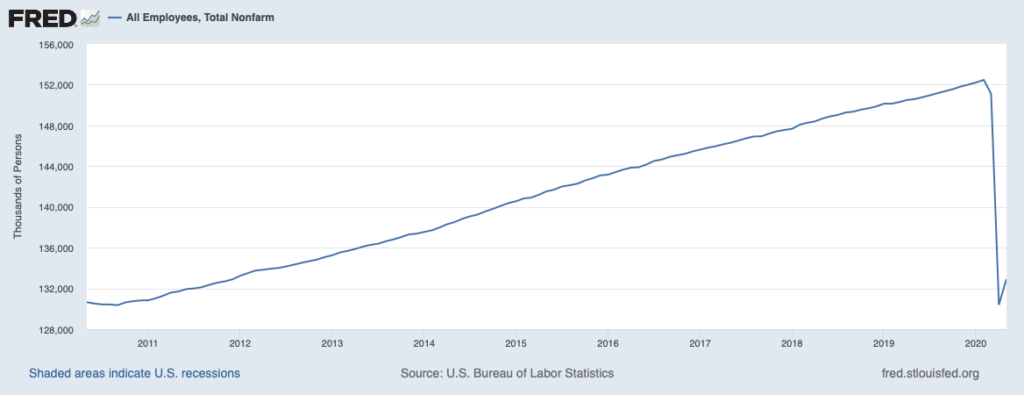

The so-called nonfarm employment “jobs numbers” reported each month by BLS at the same time that the unemployment figures are released also are derived from survey data. Different survey data. Whereas the unemployment figures are generated by the Current Population Survey (aka “Household Survey”) of 60,000 households in the United States, the figures on net new jobs each month are taken from the Payroll Survey (aka “Establishment Survey”) of 145,000 employers representing 697,000 worksites. In general, the Establishment Survey is considered a “cleaner” number than the unemployment rate, less influenced by the interpretation problems of the Household Survey. However, unlike the unemployment data, the jobs numbers are regularly revised/updated as survey responses arrive with some delay. In the latest report for May 2020, for example, the March and April job loss figures were revised downward substantially; March job loss was estimated at 1.4 million compared to an original 881,000 and April job loss was estimated at 20.7 million compared to 20.5 million. The 2.5 million increase in jobs for May can be expected to be revised in future reports, most likely upwards, as the culprit in the collection of the Establishment Survey data is the availability of someone at the surveyed company with the time to fill out the survey. One suspects that in the last three months, employers have been overburdened with things to do.

Can any insight be derived from all of this?

Yes. The picture that emerges from even problematic survey data is of an economy that sharply contracted in March and April and is now gradually beginning to return to business. Coincidentally – and with highly unusual speed and timing – the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), the official arbiter of recessions and recoveries, has just announced that the US recession started in late February. The next step by the NBER will be to identify an end to the recession, something that may take them considerably longer to do, but may ultimately place the beginning of the recovery in June or July. These designations and related employment movements should NOT be confused with a “return to normal”, however. Recovery is simply that: a beginning of a return to health, often distinguished by a considerable period of convalescence.

Disclosures

Investment advisory services offered through Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC (“Robertson Stephens”), an SEC-registered investment advisor. This material is for general informational purposes only. It does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, has not been tailored to the needs of any specific investor, and should not provide the basis for any investment decision. The information contained herein was carefully compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but Robertson Stephens cannot guarantee its accuracy or completeness. Information, views and opinions are current as of the date of this presentation, are based on the information available at the time, and are subject to change based on market and other conditions. Robertson Stephens assumes no duty to update this information. Unless otherwise noted, the opinions presented are those of the author and not necessarily those of Robertson Stephens. Indices are unmanaged and reflect the reinvestment of all income or dividends but do not reflect the deduction of any fees or expenses which would reduce returns. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Forward-looking performance targets or estimates are not guaranteed and may not be achieved. Investing entails risks, including possible loss of principal. Any discussion of U.S. tax matters should not be construed as tax-related advice. This material is an investment advisory publication intended for investment advisory clients and prospective clients only. © 2020 Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC. All rights reserved. Robertson Stephens is a registered trademark of Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC in the United States and elsewhere