February 13, 2020 – The US Treasury Department has released federal budget deficit, receipts and outlays numbers for the first four months of the government’s fiscal year (October 2019 through January 2020) and they certainly deserve attention. However, the 25% increase in the federal budget deficit over that time period is really a headline-grabbing distraction resulting from the unusual timing of monthly benefit payments (Social Security, et. al.) between January and February. The true relevance of the US Treasury Department’s release is found in the 16.4% increase in the budget deficit for the twelve-months ending in January 2020, despite a 6.7% increase in government receipts. Simple arithmetic: budget outlays outstripped this growth in receipts, rising 8.8% during the same time period.

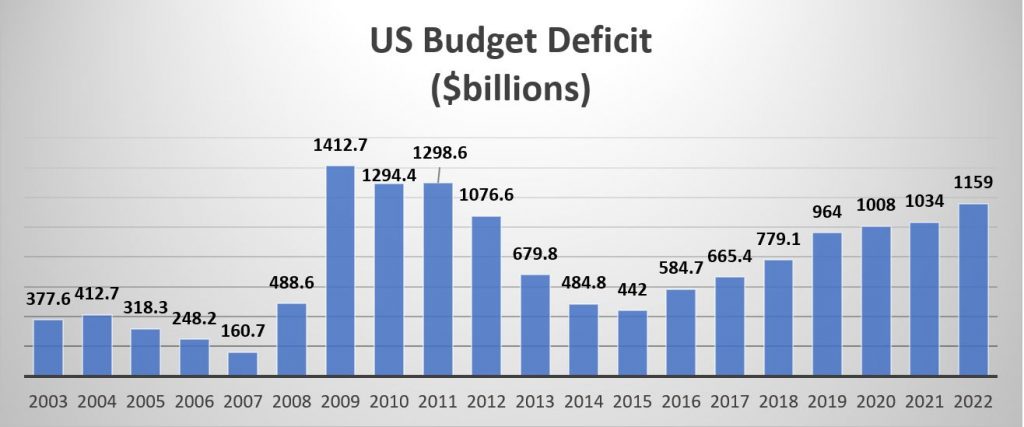

With the White House having just proposed a $4.8 Trillion budget for fiscal year 2021 (starting October 1 2020), it is worth revisiting and updating our commentary from October 2018 Deficit Attention Disorder. As mentioned in that article, the budget deficit was even then expected to hit $1 trillion in 2020. The $1.06 billion budget deficit reported for the last twelve-months was therefore no surprise to even the most casual student of Federal budgeting. Contained within the current budget proposal for 2021 is an implied formula for getting the budget deficit below $1 trillion in coming years, through sustained GDP growth of 3% and reduced outlays for various entitlement programs such as Medicaid/Medicare. Should one be willing to bet on the practicality of these budgetary assumptions – and this author is not—the stark reality is that the reduction in the budget deficit under the White House proposal is extraordinarily modest: hopefully dropping the deficit to $966 million in fiscal year 2021. It is a commentary on current economic and political realities that federal spending in this budget proposal is still projected to increase –although at a hoped-for slower pace.

The most common question about the federal budget deficit today is “Does it matter?” This question seems to be primarily derived from an intense focus on the rise in US equity markets and a very short-term concern about recessions, elections and the availability of n95 medical masks. Large and rising budget deficits are seldom worrisome to anyone but the practitioners of the dismal science (economists) and central bankers when economic times are good. In this there is an appropriate analogy (especially appropriate given the sharp rise in consumer credit card debt in the fourth quarter of 2019) to consumer debt, which not an economic constraint when household income and net worth are rising but can suddenly become a major obstacle when incomes and net worth fall during a recession.

Debt always has a price and always reduces flexibility in difficult times that may require rapid, dynamic adjustments. The immediate cost of a large and growing budget deficit can easily be borne by the current US economy. The longer term implications of monies diverted to interest payments, government utilization of liquidity that might otherwise go to private sector investments, and budgetary constraints for desired social/infrastructure improvements tend to be largely negative. It may be worth remembering that the technical term for nearsightedness, i.e. excellent vision for things held very close to the eyes, is “myopia.”

The prescription remains the same as it was in 2018: a double dose of Ritalin and Adderall and extra-strong prescription distance eyeglasses.

Source: “An Update to the Budget and Economic Outlook, 2019 to 2029”, Congressional Budget Office, August 2019

Disclosure

Investment advisory services offered through Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC (“Robertson Stephens”), an SEC-registered investment advisor. This material is for general informational purposes only. It does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, has not been tailored to the needs of any specific investor, and should not provide the basis for any investment decision. The information contained herein was carefully compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but Robertson Stephens cannot guarantee its accuracy or completeness. Information, views and opinions are current as of the date of this presentation, are based on the information available at the time, and are subject to change based on market and other conditions. Robertson Stephens assumes no duty to update this information. Unless otherwise noted, the opinions presented are those of the author and not necessarily those of Robertson Stephens. Indices are unmanaged and reflect the reinvestment of all income or dividends but do not reflect the deduction of any fees or expenses which would reduce returns. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Forward-looking performance targets or estimates are not guaranteed and may not be achieved. Investing entails risks, including possible loss of principal. Any discussion of U.S. tax matters should not be construed as tax-related advice. This material is an investment advisory publication intended for investment advisory clients and prospective clients only. © 2020 Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC. All rights reserved. Robertson Stephens is a registered trademark of Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC in the United States and elsewhere.