By Jeanette Garretty, Chief Economist

July 6, 2020 – Every soul-shaking event of the last twenty years – 9-11, the financial crisis of 2008-2009, the coronavirus pandemic – has been accompanied by a period of introspection regarding truly important things in our lives. The answers understandably are different for each individual, but there are often common themes: family, community, economic security, faith. These events also have underscored, for many people, the precariousness and capriciousness of life, motivating a desire to put one’s house in order, figuratively and literally — when financially possible, home improvement expenditures tend to rise and Marie Kondo-like organizing accelerates.

Behavioral Economics describes the human brain as having two parts, or modes of operation. The “simple, ‘fast’ brain” uses less energy and thus, quite rationally, is favored for use; it is the brain best suited for simple, straightforward analysis and action. The “complex, ‘slow’ brain” uses more energy and is only going to be used under duress or with substantial encouragement—situations where the threat is clearly and emotionally delineated, or complex analyses are illuminated by graphics, charts, pertinent humor, and interactive engagement. The widely popular use of “rules of thumb” is really the attempt to understand a complex subject with the simple brain. (See Daniel Kahneman’s seminal 2011 book “Thinking Fast, and Slow”.)

(Old joke: A man goes into a store to buy some brains. There are choices: Einstein’s brain is $2/oz., Eisenhower’s brain is $2.25/oz, Jack Welch’s brain is $2.50/oz., etc. One brain is $10/oz. “Why is that last brain so expensive?” he asks. “Oh, that brain belonged to a macroeconomist. It’s hardly been used.” This joke is entirely unsupported by the facts, by the way…)

It does not require much imagination to see how the coronavirus pandemic is completely frying our brains. The complexity of the situation – both the spread of the virus and the risks of the disease (COVID-19) and its treatments—clearly demands the engagement of the complex brain but few things are making that easy. Public health authorities report different measures, doctors debate openly about treatment efficacy, and social media makes everyone a medical expert. The energy required is often too much, and so the simple brain takes over, fixating on short, easy guidance: it’s just a bad flu, it doesn’t affect children, stay six feet apart, wear a mask, we’re all going to die someday anyway. Ultimately, the simple brain, recognizing the inadequacy of simple rules in this dire situation, gives up and retreats to controlling what it can control, with a fervor: cooking, sewing, disinfecting, cleaning the closet, checking in with old friends, editing the address book (to eliminate the annoying), drop-kicking social media, finally figuring out how to use all the features of the 65 inch 4K TV purchased last year.

The US business community appears to be catching on, exhibiting its own set of simple brain/complex brain conflicts. Perhaps because the shock of the coronavirus pandemic has been so pervasive and so beyond normal controls, the messaging and operational response of individual companies, even within the same industry, has varied widely. Pity the poor CEO, wedded to his or her one-page executive summary bulletpoints as an effective way to way to understand and make final decisions for 95% of the company problems; the pandemic falls into that other 5% with a resounding crash. Nevertheless, the potential consequences of action or inaction are the very definition of complexity. As with individuals, a path forward must be found and it will often be determined by the items that can be directly controlled in the short to intermediate term.

For some companies or organizations, the only control that appears to be available is to cease operations. This is a choice that may be forced upon them by lenders, or by regulators, or by management fatigue, but it is the ultimate employment of simplicity. A clear, definitive answer with value in its simplicity. Yet, as any economist should admonish, nothing of value is obtained for free, and so the cost of this solution is in investor, lender, and employment income dollars lost. There is value, but it comes at a very high price.

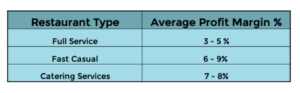

A much more interesting value obtained from simplicity is beginning to emerge, however. McDonald’s, which stripped its menu down to the basics in April, has announced it will not return salads, bagels and other items to the menu anytime soon; service times have improved by 25 seconds, errors are fewer and franchisees are happier. In other words, profit margins are better with this simpler menu. Coca-Cola will terminate its Odwalla brand line, which required special refrigerated delivery trucks, shelf life monitoring and constant flavor innovation, in July. Paper goods manufacturers are openly wondering how many different types of toilet paper and paper towels are really necessary; embossing and baby blue floral prints may not really be the most important thing to consumers right now. Brewers are starting to cut back on seasonal beers and the proliferation of labels as they respond to a “grab-and-go” grocery shopping style that is defeated by the wall of IPAs taking up so much refrigerator space in so many stores.

Source: Restaurant365.com, February 25, 2020.

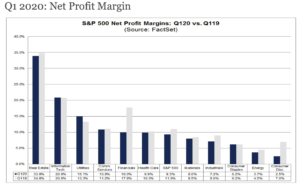

In the 1980s, the Japanese auto industry took a much less profitable US auto industry by storm, in part due an unheard-of sales approach: offer the car buyer a very limited number of models, colors and options, with a well-communicated commitment to quality and speed of service. Buying a Japanese car became insanely simple, and almost 1 million Honda Accords and Nissan Stanza’s, et.al. rolled out the door. It should not be surprising if we see manufacturers of all sorts today thinking back to examples like this, from 40 years ago, as a guide for boosting profits in the face of weakened demand. As the push for simplified product lines spreads, it is quite possible that margins in many businesses will increase.

Source: FactSet Earnings Insight, June 26, 2020

Yet, life is about consequences. Every one of these product lines is supported by finance teams, product managers, factory supervisors, marketing specialists, advertising executives, distribution workers, etc. Simplification may bring value to a variety of operations but create untold complication for the workers negatively impacted by the decisions. While the initial pandemic employment losses have been concentrated in the front-line workers of service industries, a careful reading of business layoff announcements in recent weeks illustrates that the employment cuts are beginning to be focused on middle management and corporate office personnel. These workers are likely to be older, higher paid and, despite their skills and expertise, less readily re-employable in businesses that are hunkered down and fighting for survival. Ultimately, the successful use of simplicity to boost current profitability will inevitably provide the funds to re-introduce complication, returning some of these workers to their chosen fields. As has been said from the beginning by so many wise people, the recovery of this economy is a long haul and the true perspective on what has happened is likely only to be available in hindsight.

Disclosures

Investment advisory services offered through Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC (“Robertson Stephens”), an SEC-registered investment advisor. This material is for general informational purposes only. It does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, has not been tailored to the needs of any specific investor, and should not provide the basis for any investment decision. The information contained herein was carefully compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but Robertson Stephens cannot guarantee its accuracy or completeness. Information, views and opinions are current as of the date of this presentation, are based on the information available at the time, and are subject to change based on market and other conditions. Robertson Stephens assumes no duty to update this information. Unless otherwise noted, the opinions presented are those of the author and not necessarily those of Robertson Stephens. Indices are unmanaged and reflect the reinvestment of all income or dividends but do not reflect the deduction of any fees or expenses which would reduce returns. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Forward-looking performance targets or estimates are not guaranteed and may not be achieved. Investing entails risks, including possible loss of principal. Any discussion of U.S. tax matters should not be construed as tax-related advice. This material is an investment advisory publication intended for investment advisory clients and prospective clients only. © 2020 Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC. All rights reserved. Robertson Stephens is a registered trademark of Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC in the United States and elsewhere. A1035