By Jeanette Garretty, Chief Economist

July 21, 2020 – The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) regularly prepares long-term economic growth forecasts in order to fulfill its mandate to analyze the budgetary impact of current and proposed federal legislation. These forecasts utilize generally accepted or consensus projections of population growth, demographic trends, labor force participation rates, productivity, and US long-run equilibrium growth rates, as well as various assumptions regarding inflation and interest rate trendlines. An overriding caveat of CBO forecasting is that fiscal policy must be taken as given – that is, the metrics of federal government spending, tax structure and other fiscal variables, present and future, are determined by existing legislation only. No assumptions can be made regarding likely changes in future economic policy. Almost by definition, therefore, the out-years of a CBO 10-year forecast are wrong. Nevertheless, that does, in some sense, capture the essence of its value. If one doesn’t like what one sees in the long-term extrapolation of current trends and policy – most notably, the outlook for budget deficits and economic growth – then one can look to Congress to change the view.

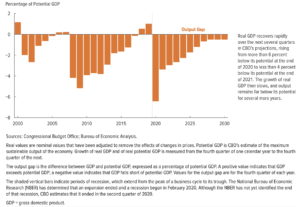

The most recent CBO update to its long-range forecast was prepared in early July. On one level, the forecast provides encouragement for the near-term outlook for economic growth, and describes an economy that reassuringly will return in seven years to the long-term trajectory for real potential GDP growth that existed before the pandemic.

Growth of Real GDP and Real Potential GDP

Source: Congressional Budget Office, “An Update to the Economic Outlook: 2020 to 2030,” July 2020. Shaded bars represent actual and estimated recession periods

A slightly less rosy picture is presented by looking directly at the output gap (real GDP versus real potential GDP) as opposed to the growth rate of GDP. As illustrated by the following chart from the same July CBO forecast, even GDP growth rates higher than the projected growth rate of potential GDP leave the level of real output notably lower than potential GDP for the whole ten years. The level of output is a much more visceral concept than the growth rate: it means the breadth and depth of the job market, then strength of income, and standards of living.

However, there is an even greater problem. The July Economic Outlook does not contain budget deficit projections (those will be provided by the CBO in August). In January 2020, before the sharp increase in pandemic-related fiscal spending, the CBO projected an average budget deficit of $1.3 trillion annually, totaling $13.1 trillion across the 2020-2030 forecast period. In that context, the illustrated real potential annual GDP growth of barely 2% is cause for considerable concern. How can the budget deficit be reduced, without draconian tax increases, if potential economic growth cannot be raised to at minimum the 4% growth of the late 1990s?

Potential GDP growth can be understood in remarkably simple terms: labor force growth + total productivity growth. For example, if US labor force growth is 1.1% per annum — the Bureau of Labor Force Statistics (BLS) figure for 1998-2008—and total productivity growth is 2%, then real potential GDP growth is 3.1%. Since the Great Recession, productivity growth has averaged closer to 1.5% and at present, BLS is forecasting labor force growth of 0.5% for the coming decade. What would one like to change to raise potential GDP growth: labor force growth or productivity growth or both?

Demographic trends are not as immutable as one might think. Labor force growth can be altered through immigration policies, subsidized child care, improved health and education & technical training. Yet even returning to the labor force growth rates of the pre-Great Recession decade will only support a 2.5% growth rate in real potential GDP if productivity growth cannot somehow be accelerated.

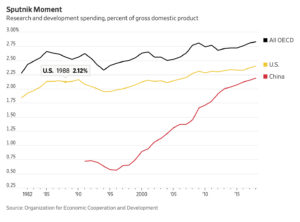

There has been much finger-pointing regarding the lack of productivity growth over recent years. A mismatch between education and job skills and the needs of the fastest growing industries is generally considered a possible culprit. But the lackluster pace of US business investment in the 21st century is hard to ignore. Whereas business fixed investment commonly grew in the 10% range in the 1980s and 1990s, it has subsequently risen closer to 5% per annum on average, with much more pronounced negative swings. This development is even more puzzling when one considers that the “hurdle rate” for business investment decisions, the 10-Yr. Treasury rate, has been incredibly low for much of this same period. Since business fixed investment is a domestic concept, it may very well be that investment spending by US businesses has remained at previous levels, but not in the United States (measures of US business investment activity, including durable goods orders, are only for domestic expenditures, not expenditures deployed in non-US locales.)

Irrespective of the cause, it is entirely appropriate to view this as a call to action. A ballooning budget deficit and ageing population supported by a near-static prime working age (16-54 years old) employment base can only lead to onerous tax burdens shouldered by the next generation.

To say that life moves in mysterious ways is perhaps the understatement of this century. The current focus on an (undefined) new normal, on new ways of working, on public health and on better working conditions may serve to move business investment in a direction it could not find on its own. The meat packing industry, for example, is discovering a need to make greater investments in robotics and robotic research (currently available robotics for meat-cutting are far from perfect) because of the ravages of coronavirus on its labor force. Companies finding greater acceptance of, and willingness to invest in, a remote workplace make it possible for more people (women, the handicapped, the geographically constrained) to become highly productive members of the labor force. A shifting of production facilities from traditional locations, including overseas, means the building of new, modern, more productive plants. Investment tax credits have always been a controversial solution to boosting investment growth (many economists question their effectiveness) but it is entirely possible that, recognizing the need to raise potential GDP growth through productivity growth, there will be economic policies designed to encourage a “moon shot” effort of sustained investment for future growth.

None of this is being much discussed during our intense focus on simply surviving the peril of the coronavirus pandemic. That is understandable. With the return of economic growth in the US, China and Europe, however, there will be a turn to the future and hopefully a discussion of what is necessary for both now and then. The future described by the statistics of the BLS and the CBO is not set in stone.

Disclosures

Investment advisory services offered through Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC (“Robertson Stephens”), an SEC-registered investment advisor. This material is for general informational purposes only. It does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, has not been tailored to the needs of any specific investor, and should not provide the basis for any investment decision. The information contained herein was carefully compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but Robertson Stephens cannot guarantee its accuracy or completeness. Information, views and opinions are current as of the date of this presentation, are based on the information available at the time, and are subject to change based on market and other conditions. Robertson Stephens assumes no duty to update this information. Unless otherwise noted, the opinions presented are those of the author and not necessarily those of Robertson Stephens. Indices are unmanaged and reflect the reinvestment of all income or dividends but do not reflect the deduction of any fees or expenses which would reduce returns. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Forward-looking performance targets or estimates are not guaranteed and may not be achieved. Investing entails risks, including possible loss of principal. Any discussion of U.S. tax matters should not be construed as tax-related advice. This material is an investment advisory publication intended for investment advisory clients and prospective clients only. © 2020 Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC. All rights reserved. Robertson Stephens is a registered trademark of Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC in the United States and elsewhere. A1039