Jeanette Garretty, Chief Economist, September 9, 2020

Anyone who has taken a first-year economics course has heard about what is sometimes called the micro-macro paradox, where completely valid decisions by individual actors in the marketplace lead, in the aggregate, to market conditions that invalidate those decisions (Note: the paradox was alternatively defined by Paul Mosley in 1987 to apply to foreign aid and economic growth and is not the subject of this discussion.) Often, the examples given are agricultural, as the planting decisions of a large number of farmers must be made well in advance on the assumption of a crop price that may not be obtained if the ultimate supply is greater than the demand. In the late 1970s, Bank of America economist Eric Nickerson co-authored a well-received report on the California wine industry, forecasting a significant increase in wine consumption in the United States, with rising revenues for California wineries and grape growers as a result. Wine consumption certainly increased, but —encouraged by the report’s forecast— wine grape acreage exploded and new wineries popped up throughout the state, causing supply to far outstrip the increased demand. For a few years, no Bank of America economist voluntarily identified themselves in a California winery tasting room, so great was the anger about the falling prices and numerous bankruptcies that crushed so many well-intentioned dreams.

Planning is a necessity for any business. Inventory has to be ordered, equipment has to be bought, people need to be hired, budgets need to be set. The typical corporate business planning cycle has not changed much over the years; division managers and lines of business are given basic financial assumptions in July and told to submit their preliminary business plans for the coming year to corporate headquarters in September. Those plans are reviewed over a six- to eight-week period before being finalized sometime around Thanksgiving, with division heads frequently being asked to revise the plans to show greater growth and/or profitability. Even in relatively benign economic environments, layoffs and business line restructurings tend to be announced as this planning process unfolds; by September, every business leader is thinking mostly about hitting the ground running in January.

In this crazy, pandemic year of extreme economic uncertainty, planning for 2021 is a daunting effort for company management teams. The truly brave might be willing to prepare a plan for a world without the coronavirus and with robust economic resurgence, but the planning process itself discourages that kind of bravery and tends to favor more cautious, linear thinking (i.e. assumptions of more-or-less straight-line extrapolations of current trends.) Chief financial officers always provide critical guidance at times like this and with access to capital (bank loans, equity, etc.) and long-term financial survival dominant questions at the moment, they hold much of the power in setting the course for 2021.

On September 3, the Association of International Certified Professional Accountants (AICPA) published its third quarter U.S. Economic Outlook Survey of executives regarding economic conditions and company-specific issues such operating costs and liquidity. Sixty-seven percent of the respondents are from private companies and the majority are chief financial officers or controllers. This particular survey is noteworthy in that it was taken between July 28 and August 18, coinciding with the beginning of the business planning cycle.

One especially interesting finding of the survey is that executives anticipate labor costs will rise over the next twelve months, mostly due to increased salaries and benefits. This would seem more than a bit counterintuitive in light of the still high unemployment rate, but appears to reflect the actual experience of companies as the US economy has opened up, a much-publicized example of which is the increase in pay and benefits Amazon found itself needing to provide to its distribution center workers. Labor cost increases emerge in the AICPA survey as one of the top three issues for the chief financial officers and other executives of the survey, along with “domestic economic growth” and “domestic political leadership.” “Availability of skilled personnel” rounds out the top four.

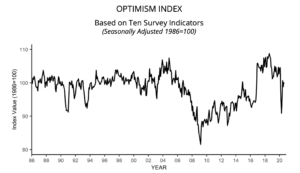

Another just-released survey of note comes from the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB). The NFIB’s August 2020 Small Business Optimism Index (© NFIB Research Center. ISBS #0940791- 24-2) rose modestly, pushed up by the expectations of a growing number of businesses (but not a majority) to increase hiring and inventories and held back by weak capital spending and pessimism about sales growth. More so than the AICPA, the NFIB survey captures significant differences between industries, such as the growth in construction and the difficulties in hospitality. Yet, the NFIB respondents also cited labor costs as a significant area of concern, with almost twenty percent having raised compensation this year, another fourteen percent expecting to raise compensation going forward and twenty-one percent naming “finding qualified labor” as their top business problem.

Source: NFIB Small Business Economic Trends, August 2020

These preliminary insights into the thinking of senior management teams signal, not surprisingly, a concern about profit margins. If labor costs are rising while sales growth remains modest, passing along profit-margin-preserving price increases to the buyer will depend heavily on the relative market power of the business; some will have it and some won’t. The good news is that there is no clear messaging that everyone intends to raise prices to protect profits, which could quickly put businesses into that aforementioned micro-macro paradox – otherwise known as the law of unforeseen consequences. Increases in final product prices to protect margins against erosion from increased input costs ignores the reality that in an economy operating well below full-employment (of both plant, equipment and labor), the negative effect of price increases on demand can serve to lower the real goal: profits.

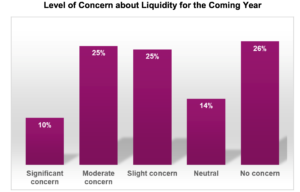

Another take-away from these surveys is a fairly realistic assessment of the economic environment, coupled with a strong sense of being able to “manage through.” No doubt this attitude is assisted immeasurably by the current ability to access capital. No chart is more remarkable after everything the US economy has been through in 2020 than the following from the AICPA Outlook:

In the NFIB survey, thirty-one percent of small businesses indicated that all their credit needs were met and fifty-three percent (!) said that they were not interested in a loan. Business planning done without the complication of financial stress is almost always better business planning.

A final observation, however, about where the careful thought of these business executives might go awry. It would seem that many might be planning for a long-term business model of doing more, differently and with less, recognizing in turn that this will require a skilled labor force that costs somewhat more. It is the business model that has carried these businesses through the challenges of the pandemic and it is supremely logical to look to it for the future. But in drawing a picture of business profitability and growth based on increased productivity, one element of the picture is consistently lacking: capital spending. Both the AICPA and the NFIB highlight the lack of investment in plant and equipment expected for the near future, with the NFIB economists making the cogent statement that:

Forty-seven percent {of survey respondents} reported capital outlays in the last 6 months, down 2 points from July. Capital expenditures are 16 points below January’s level. These low levels of investment are contributing to low GDP growth and will retard productivity improvements over the next year . . . The enemy of investment is uncertainty about sales, regulations, Covid-19, elections, and more.

A failure to invest adequately in plant and equipment to support a new business model will almost certainly generate disappointment in the long-term profits expected from that business model. Traditionally, the rate on the ten-year US Treasury Note is used as the hurdle rate for a business investment; finding capital investments whose returns exceed the present .7% (or commonly forecast 1.25% at the end of 2021) should not be difficult even with appropriate discounting for the uncertainty of “sales, regulations, Covid-19, elections, and more.” (With the exception of Covid-19, those uncertainties always exist.) If the business plans formulated for 2021 contain limited capital spending budgets, then it is quite possible that productivity and economic growth might fail to meet expectations, impacting profits adversely.

Disclosures

Investment advisory services offered through Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC (“Robertson Stephens”), an SEC-registered investment advisor. This material is for general informational purposes only. It does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, has not been tailored to the needs of any specific investor, and should not provide the basis for any investment decision. The information contained herein was carefully compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but Robertson Stephens cannot guarantee its accuracy or completeness. Information, views and opinions are current as of the date of this presentation, are based on the information available at the time, and are subject to change based on market and other conditions. Robertson Stephens assumes no duty to update this information. Unless otherwise noted, the opinions presented are those of the author and not necessarily those of Robertson Stephens. Indices are unmanaged and reflect the reinvestment of all income or dividends but do not reflect the deduction of any fees or expenses which would reduce returns. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Forward-looking performance targets or estimates are not guaranteed and may not be achieved. Investing entails risks, including possible loss of principal. Any discussion of U.S. tax matters should not be construed as tax-related advice. This material is an investment advisory publication intended for investment advisory clients and prospective clients only. © 2020 Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC. All rights reserved. Robertson Stephens is a registered trademark of Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC in the United States and elsewhere. A1062