By Jeanette Garretty, Chief Economist

August 27, 2021 – There is a great deal of attention currently directed to the issue of US inflation. Depending upon the chosen metric— CPI, core CPI, year-over-year, month-over-month– the rate of inflation is somewhere between

3.5% and 5.5%, and well above the 2010-2020 average of approximately 2%. Although the Federal

Reserve and many other economists have attributed the increase in inflation to “transitory” factors, such

as pandemic-related supply constraints and the reluctance of workers to return to possibly unsafe workspaces,

there are others debating the possibility of more permanent changes being brought about by the

slow growth or actual decline of a demographically-challenged labor force. Historically, economists (including,

and most notably, those at the Federal Reserve) have not worried much about US inflation numbers

unless accompanied by rising labor costs, as measured by a battery of numbers provided by the Bureau of

Labor Statistics (BLS): the Employment Cost Index (ECI), Unit Labor Costs and Average Hourly Earnings.

The rationale behind this focus has been that labor constitutes the single greatest component of production

costs and is “sticky”, i.e. unlike direct materials costs or even the (in)famous “overhead”, labor costs don’t

easily or immediately decline with changing market conditions. Clearly, this understanding of labor does

not match-up well with the so-called gig economy or research- and capital-intensive technology sectors, but

it is still considered a fair conceptualization of the US employment and production landscape.

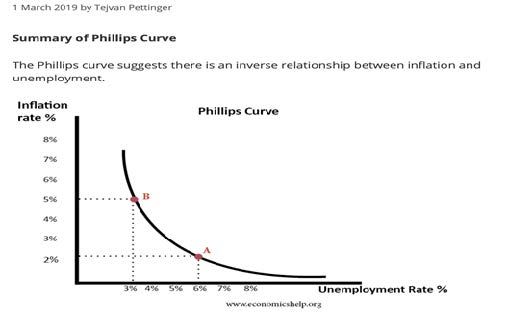

For many, the relationship between labor costs and inflation was once summarized by a construct known

as the Phillips Curve. Wikipedia provides a discussion of the Phillips Curve that perhaps only an economist

could love, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phillips_curve, but it’s worth a read to appreciate the actual complexity

of the inverse relationship between unemployment rates and the rates of increase of money wages

first described by William Phillips in 1958. Suffice to say that the simple curve that many of us first thought

we saw in an Econ 101 course,

purporting to relate unemployment

rates to inflation rates, was overly

naïve at best and downright inaccurate

in most cases. Nevertheless,

the general idea persists and led to

much angst as the unemployment

rate dropped across the last, long

economic expansion and wages

remained stagnant and inflation dormant.

Now, there is a thought that

the Phillips Curve has found its day,

and as the unemployment rate is

falling, wages in fact are accelerating

and inflation on the rise as well.

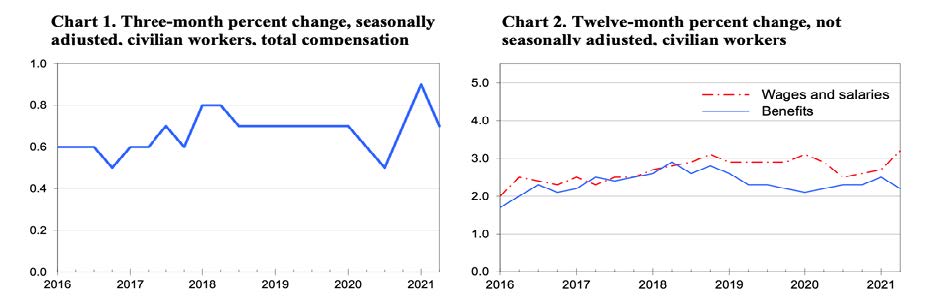

On July 30, 2021, the BLS released data showing the Employment Cost Index rose 2.9% in the 12 months between June 2020 and June 2021. Interestingly, the 12-month increase for the period from June 2019 to June 2020 was not appreciably different, at 2.7%. Looking back even further into the pre-pandemic era, once sees a fairly stable, non-accelerating ECI (https://www.bls.gov/news.release/eci.t01.html).

The critical missing link between wages/total employment costs (notice in Chart 2 above the intermittent

divergences between wages/salaries and benefits, both constituting total employment cost) and inflation is

productivity. Should an employee approach their employer with a request for a 10% increase in pay and

the employer responds that this is impossible because final product prices can only be raised 2%, the proper

rejoinder is for the employee to point out their 20% increase in productivity; a 10% raise in that circumstance

would still represent a 10% decline in labor cost (Please let me know if you try this and it works.)

Another way to appreciate the role of productivity is to consider the experience of technology companies

employing a high paid workforce while producing products with precipitously declining prices – and yet

posting substantial profits. Over time, the rising wage rates postulated by the Philips Curve can be – but

will not necessarily be—matched by improvements in the capital stock and labor force quality (education,

training, management approaches, etc.) that lead to higher productivity, mitigating or negating the upward

pressure on price levels.

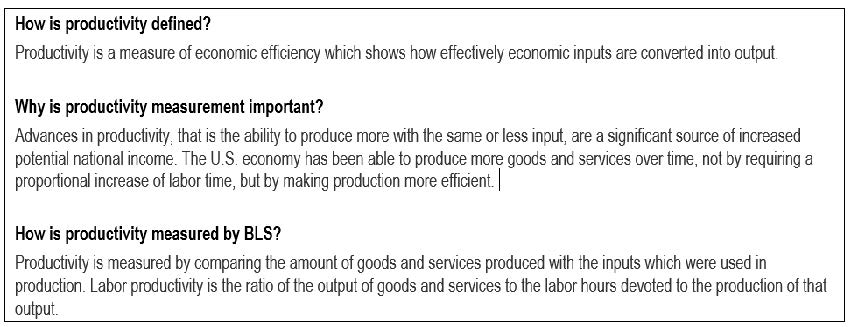

For as much discussion of inflation and supply-chains and labor force participation rates as currently exists,

it is extraordinary that there is not a more explicit discussion of productivity given its centrality to the issue

of economic growth and price stability. In part, this can be understood because of the sheer difficulty of

measuring productivity as one would tend to think of it, via direct observation and in association with labor.

Essentially, reported productivity numbers are a purely arithmetic result of the relationship between inputs

and GDP. Consider the following commentary from the BLS website, which, while succinctly describing

the importance of the concept, also explains that raising productivity is as simple as getting GDP to go up

while not employing appreciably more workers. Productivity quite often rises in the very early stages of an

economic recovery as factories are cranked up to full-operation levels with the existing workforce working

the same number of hours. Similarly, productivity often falls at various points of an expansion when GDP

growth slows due to trade issues, natural disasters, etc.

Nevertheless, measurement problems are not an argument against a robust consideration of what productivity

can do for us – and to us. To the extent that rising wages may reflect a tight labor market resulting

from 1) an aging population, 2) a skill/education mismatch with currently available jobs and/or 3) a potential

workforce made unavailable and unproductive by social realities such as lack of childcare or prescription

drug abuse, it is reasonable to expect an investment in equipment and processes per the degree to which

producers believe that these problems cannot be otherwise fixed in the medium-to-long term. This is NOT

why the Federal Reserve uses the term “transitory” to describe the current set of inflationary pressures; the

Federal Reserve remains, as it should, acutely focused on the near-term outlook for inflation and the implications

for monetary policy. But a slightly longer and wider lens calls into question any analogies to the

inflation patterns of the late 1970s, when the US capital stock was aged (e.g. steel blast furnaces), unions

were a dominant force, innovation took much longer to come to market and artificial intelligence was a sci-fi

dream.

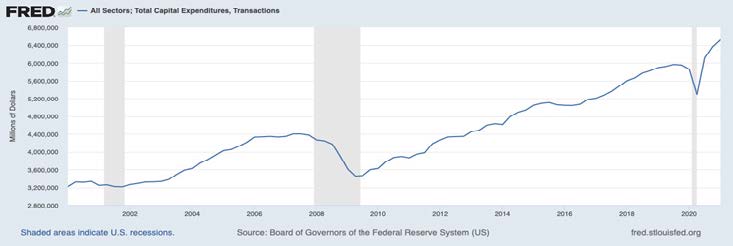

There was a popular view in the late 1970s, hard to conclusively prove, that labor was being substituted for

capital because labor did not use the high-priced energy required by machinery and equipment (remember,

in December 1979 Saudi Arabia raised oil prices approximately 30%). Today, forces would seem to

be quite the opposite. A capital spending “boom” has yet to convincingly materialize, but the early signs are

there.

As with so much else, the pandemic seems it will push economies and their participants more quickly into a future that was only hinted at prior to January 2020; note that the upward slope of the capital expenditures chart line has increased of late, exhibiting a pattern quite different from the last recession in 2008-2009. With robust corporate earnings and improving economic growth forecasts, private sector investment is unlikely to slow down. Fiscal policy proposals in the United States, focused on infrastructure and, more controversially, childcare and tuition-free community college, are examples of public investment aimed at the same goal: raising productivity. And every child going off to school this month represents an investment in a future where increased employment and rising wages be possible without the threat of accelerating inflation. Because of productivity. Hope is not a strategy, but strategy can be legitimately derived from hope.

Disclosures

Investment advisory services offered through Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC (“Robertson Stephens”), an SEC-registered investment advisor. Registration does not imply any specific level of skill or training and does not constitute an endorsement of the firm by the Commission. This material is for general informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment, tax or legal advice. It does not constitute a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, has not been tailored to the needs of any specific investor, and should not provide the basis for any investment decision. Please consult with your Advisor prior to making any Investment decisions. The information

contained herein was carefully compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but Robertson Stephens cannot guarantee its accuracy or completeness. Information, views and opinions are current as of the date of this presentation, are based on the information available at the time, and are subject to change based on market and other conditions. Robertson Stephens assumes no duty to update this information. Unless otherwise noted, the opinions presented are those of the author and not necessarily those of Robertson Stephens. Indices are unmanaged and reflect the reinvestment of all income or dividends but do not reflect the deduction of any fees or expenses which would reduce returns. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Forward-looking performance targets or estimates are not guaranteed and may not be achieved. Investing entails risks, including possible loss of principal. Alternative investments are only available to qualified investors and are not suitable for all investors. Alternative investments include risks such as illiquidity, long time horizons, reduced transparency, and significant loss of principal. This material is an investment advisory publication intended for investment advisory clients and prospective clients only.

Robertson Stephens only transacts business in states in which it is properly registered or is excluded or exempted from registration. A copy of Robertson Stephens’ current written disclosure brochure filed with the SEC which discusses, among other things, Robertson Stephens’ business practices, services and fees, is available through the SEC’s website at: www.adviserinfo.sec.gov. © 2021 Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC. All rights reserved. Robertson Stephens is a registered trademark of Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC in the United States and elsewhere. A1149