By Jeanette Garretty, Chief Economist

March 15, 2023 – My career in finance is almost exactly coincident with the deregulation of the banking industry. The Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 allowed depository institutions a freer hand in setting depository account interest rates, partly in response to the innovation of the enormously popular CMA (“Cash Management Account)— aka “sweep account” — by Merrill Lynch in 1977. The CMA account was a blending of banking and brokerage services that some feel achieved full fruition in 1999 with the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act that overturned much of the Glass-Steagall Act and allowed banks to almost seamlessly offer commercial banking, investment and insurance services to their clients. In between, another notable deregulation milestone was the removal of McFadden Act statutes preventing branch banking across state lines in 1994. Every step in deregulating US banking activities was adopted in the belief that the actions would 1) improve the safety of the system (via diversification of revenue sources), 2) increase innovation that benefits consumers and businesses (by allowing for the introduction of new products and competitive pricing) and 3) enhance the implementation and management of monetary policy (by recognizing a broader definition of the money supply and providing more “levers” for the Federal Reserve to pull for the achievement of a desired result.)

For most people, there is little memory of a banking industry that was once regulated as a utility, with little differentiation in product and regulator-approved pricing. At the same time, most people also still think of banking as something to which everyone should have access, and which exists primarily to serve the public by providing a safe, secure necessity known as a checking account. In 2008-2009, and again this week (but for a different reason), questions about the safety of one’s funds in a bank expose how little the public really knows about the business model of banking and how much the public feels it is entitled to have a bank account in which there is full faith and trust.

“Trust” is a concept surprisingly difficult to define. There are whole fields of academic research devoted to the concept. The simplest explanation of how one establishes trust in an individual or entity is for that individual or entity to do exactly what has been promised, consistently and over time. Obviously, if the trust in question is that there will be funds available in an account, for use when needed by the owner of those funds, then the limitations of FDIC deposit insurance present an obstacle to that strongly-desired trust.

One way of understanding the modern supervisory role of The Federal Reserve, the FDIC and the OCC (Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, a bureau of the Dept. of the Treasury) is that, as deregulation of bank activities proceeded, the need for sophisticated supervision of those activities increased. The dominant idea, for many years, was that the regular and often intense scrutiny of the OCC, via annual and sometimes quarterly banking reviews, coupled with Fed oversight and FDIC monitoring, would identify threats to the security of the deposit base and provide immediate remedies. The OCC initially concentrated on lending activities, but by the 1990s, had expanded to more general audits of operations and management. These reviews could be brutal and the cause of no small amount of consumption of Pepto Bismol by bank asset/ liability and credit committees. When Gramm-Leach-Bliley came along, it was speculated that it was now the supervisors turn to take antacids. State-chartered banks, by the way, were never supervised in this way — sometimes notoriously so— under the theory that they weren’t large enough or complex enough to require such thorough monitoring.

An aggressively libertarian view of the world, which often shows up in university-level money & banking courses, is that little regulation, no insurance, and only modest amounts of supervision are required. Banking should be like any other industry, free to innovate and subject to the same accounting procedures as nonfinancial corporations. Customers should have the responsibility to read financial statements for themselves and make their own judgement as to the stability of the institution and the associated safety of their deposits. To a certain extent, this is what happened to Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) on March 9, 2023. Customers made attempts to analyze the bank’s financial statements and made snap decisions (assisted by social media “experts”) about what they thought they saw. It was SVB’s misfortune to have a client base precocious enough to attempt this analysis on the fly; most people will not have the capability or desire to undertake such an exercise as it relates to a plain-vanilla checking account. Assuming that a majority of individuals and small businesses are going to be able to properly analyze the risk of their depository institution is, quite simply, intellectual arrogance.

So . . . Into this breach has now stepped the joint statement on Sunday, March 12 by the Treasury, Federal Reserve and FDIC. In establishing full coverage of depositor balances at risk in the Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank failures, above the previous FDIC $250,000 per account per beneficiary (accounts held jointly have $500,000 of coverage and accounts held by a revocable trust may have considerably more coverage than $250,000, dependent upon the number of death beneficiaries of the revocable trust), these regulatory/supervisory bodies have effectively met the afore-mentioned faith and trust expectations of the two banks’ customers. The unanswered question is whether this action also represents the most significant re-regulation of banking since the Great Recession, possibly the most astounding change to bank deposit activities since the 1980 Deregulation and Monetary Control Act.

The joint statement is explicitly limited to the depositors of SVB and Signature; it is not a universal statement of deposit insurance for the depositors of all banks. The support provided to depositors of other banks caught-up in the crisis of confidence generated by the SVB and Signature failures is a massive line of credit from the Federal Reserve and the Treasury offered to banks, savings associations, credit unions and other institutions in the event of unusually high depositor demands for funds. This line of credit, collateralized by bank bond holdings, eliminates the need for banks to recognize a loss (due to rising interest rates) in a hold-to-maturity portfolio needing to be sold in order to obtain the liquidity required to give depositors complete access to their funds. Yet the issue of whether the Fed, Treasury and FDIC have set a precedent on making all depositors whole remains a valid subject of discussion.

It seems highly likely that a populist response to the joint statement would focus on the bottom-line important to most people: “My deposits are safe.” The further likely reaction would be “It’s about time someone recognized this is what I want.” Can the Fed, Treasury and FDIC really ignore this unvoiced-but-obvious reaction?

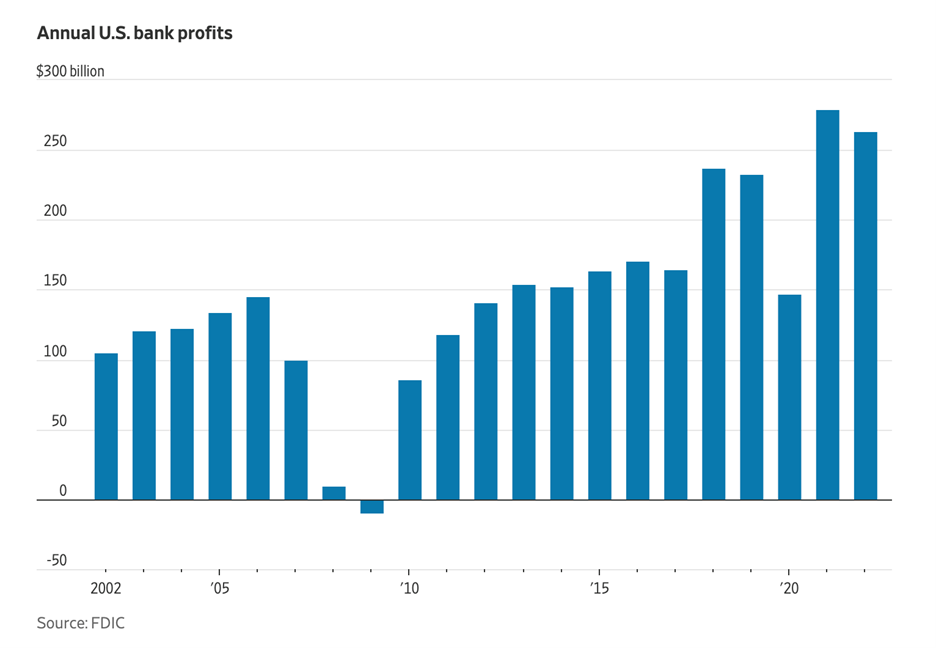

The problem, of course, is how to pay for what people may want—and as certain as it may be that people want a full guarantee of their deposits, it is equally certain that people have no comprehension of the cost of providing such a full guarantee. Banks do. As of the end of 2022, the FDIC’s Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF) balance stood at $128.2 billion, representing the net accumulation of premiums paid by covered institutions, plus any income from the US Govt. Treasuries in which the DIF is invested. Any expansion of FDIC insurance, possibly to either higher balances or to all consumer deposit accounts would demand an increase in premium amounts paid by covered financial institutions. In 2015, a paper by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis reported that the assessed cost of supervising 69 of the largest and/or most complex financial institutions— i.e., the direct costs borne by the banks– was $472 million; most bankers would hasten to explain that including their indirect costs, such as personnel to prepare reports for supervisors, would push the cost substantially higher. The direct and indirect costs of supervision, including revenue lost due to supervisory-mandated restrictions on business activity, are a major reason that banks argue against increased supervision and make great efforts to avoid the “Systemically Important Bank” designation that has the most rigorous level of supervision. Smaller financial institutions, still supervised on the basis of an assumption that they are less complex and therefore less risky, have historically been extremely aggressive in protecting their profitability against the additional costs and business limits that might be imposed.

One way to think about the recent decline in bank equity prices, especially the sharp declines in the equity prices of regional banks, is that the market is pricing in a change in future bank costs and profitability associated with greater supervision or higher FDIC insurance premiums or both. Nothing as yet has been announced, but there has been much discussion of the impact of 2018 Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief and Consumer Protection Act. which relieved banks such as SVB and Signature Bank from the supervisory requirements of the SIB category, including stress tests, by raising the size requirement from $50 billion to $250 billion. Reversing the 2018 action would require legislation that might be difficult to obtain in light of the extremely effective lobbying efforts of the American Bankers Association, despite the current increased scrutiny of smaller banks as a source of risk. On its own, however, the Fed can take action to tighten the supervision of banks at all levels. The FDIC, as an independent agency created by Congress, may have to move carefully in changing insurance premiums and covered deposit amounts, but does have some independent authority for its actions (as witnessed with the Joint Statement issued on March 12.) After the Great Recession there was popular demand for “reigning in” the large banks and ensuring greater stability in the banking system. It is quite possible that the SVB and Signature Bank failures, and questions about other regional banks, will similarly boost the calls for increased stability and safety in the banking industry, at an increased cost to banks and changes in their business models.

As we think about how much has changed, and may yet change, in this decade – higher inflation, much lower population growth, the end of “easy money”, the practical emergence of AI (artificial intelligence), revised globalization, trade barriers, “Great Power” conflict, etc. – it is worth giving some consideration to how banking and banking regulation may need to change. The most alarming thing about the SVB collapse was the speed and manner in which it happened. A banking crisis more reminiscent of the meme-stock trading follies than anything else, fueled by mobile banking, phone apps and a tsunami of social media commentary moving faster than the human brain can process (intelligently.) While greater transparency is sometimes suggested as the answer, the challenge remains of meeting the expectations of a population that just wants a safe and reliable checking account, without much work on their part. Higher capital requirements, greater supervision, expanded insurance . . . it’s likely all in the mix right now. It has been more than 40 years, going all the way back to that fateful moment in 1980, since the United States approached banking as a utility; even utilities aren’t really treated as utilities anymore. Yet this may be where we are headed. Stay tuned.

Disclosures

Investment advisory services offered through Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC (“Robertson Stephens”), an SEC-registered investment advisor. Registration does not imply any specific level of skill or training and does not constitute an endorsement of the firm by the Commission. This material is for general informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment, tax or legal advice. It does not constitute a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, has not been tailored to the needs of any specific investor, and should not provide the basis for any investment decision. Please consult with your Advisor prior to making any Investment decisions. The information contained herein was carefully compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but Robertson Stephens cannot guarantee its accuracy or completeness. Information, views and opinions are current as of the date of this presentation, are based on the information available at the time, and are subject to change based on market and other conditions. Robertson Stephens assumes no duty to update this information. Unless otherwise noted, any individual opinions presented are those of the author and not necessarily those of Robertson Stephens. Indices are unmanaged and reflect the reinvestment of all income or dividends but do not reflect the deduction of any fees or expenses which would reduce returns. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Forward-looking performance targets or estimates are not guaranteed and may not be achieved. Investing entails risks, including possible loss of principal. Alternative investments are only available to qualified investors and are not suitable for all investors. Alternative investments include risks such as illiquidity, long time horizons, reduced transparency, and significant loss of principal. This material is an investment advisory publication intended for investment advisory clients and prospective clients only. Robertson Stephens only transacts business in states in which it is properly registered or is excluded or exempted from registration. A copy of Robertson Stephens’ current written disclosure brochure filed with the SEC which discusses, among other things, Robertson Stephens’ business practices, services and fees, is available through the SEC’s website at: www.adviserinfo.sec.gov. © 2023 Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC. All rights reserved. Robertson Stephens is a registered trademark of Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC in the United States and elsewhere.