By Avi Deutsch

September 14, 2023

Summary of Key Points:

- As the immediate battle against inflation nears its conclusion, the term natural interest rate is increasingly used by economists and pundits discussing the Fed’s future rate path.

- The natural interest rate refers to a federal funds rate that neither stimulates nor constrains the economy, and instead keeps it at full employment and low inflation.

- The natural rate trended downward between 1960 and 2007, culminating in a precipitous drop in 2008, after which the rate remained depressed. Most of this decrease can be attributed to slowing economic growth.

- More recently, as the economy has shown outstanding resilience in the face of steep interest rate hikes, some economists are arguing the natural rate may be rising again.

- Uncertainty around the trajectory of the natural rate, coupled with the Fed’s desire to make sure inflation has been subdued, will provide investors with both opportunities and risks.

_________________________________________

Over 18 months into this tightening cycle, and with headline inflation down to 3.2% as of July, many are wondering when the Fed funds rate will reach its terminal rate, the peak rate of this tightening cycle. But as investors look further out, the question of where interest rates will settle in the coming years depends on factors beyond inflation. Over longer time horizons, the Fed’s interest rate strategy is strongly influenced by a benchmark for all rate decisions named the natural interest rate or r*.

The natural interest rate is broadly defined as the real short-term interest rate that neither stimulates nor contracts the economy. It is not only the Fed’s long term target rate, but also tells the Fed’s leadership if the current fund rate is slowing down or accelerating economic growth. This note will explain how this rate is estimated, what economists are saying about its future, and what this means for investors.

Understanding the Natural Interest Rate

Underpinning the natural interest rate is the assumption that every economy has an output level at which the economy is growing at an optimal rate. In this economy, inflation is low, and so is unemployment. The economy isn’t growing fast enough that employers are forced to continuously raise wages, which could drag the economy into an inflationary cycle. It also isn’t growing so slowly that unemployment rises to unacceptable levels and hurts demand. This optimal economy is also referred to as the trend rate of growth, or the long-term growth rate.

The role assigned to the Fed is to balance inflation and unemployment by minimizing the gap between the economy’s actual output and the trend rate of growth. Think of the Fed as the driver of a combustion-engine car designed to operate at a given level of RPMs. Give the car too much gas, and the engine will overheat. Give the car too little gas, and the engine will start to stall. Now imagine that the car is finicky, the road is windy, and the driver is blindfolded, and you have a sense of the challenge the Fed is facing.

If the above sounds like an exaggeration, consider that the trend rate of growth is constantly changing based on demographic trends, saving rates, changes in productivity, and technological improvements. Beyond these changes, the economy is influenced by myriad external factors, from global pandemics to regional wars. And finally, the Fed is working with imperfect data and complex models that are themselves based on many simplifying assumptions.

A Recent History of the Natural Interest Rate

The term natural interest rate was first proposed by Knut Wicksell in 1898, and though it cannot be directly observed, economists use a variety of different models to estimate it. The largest driver behind the natural interest rate is the trend growth, the economy’s growth sweet spot, which in turn is affected by technology, demographics, business and public sector investments, and saving rates.1

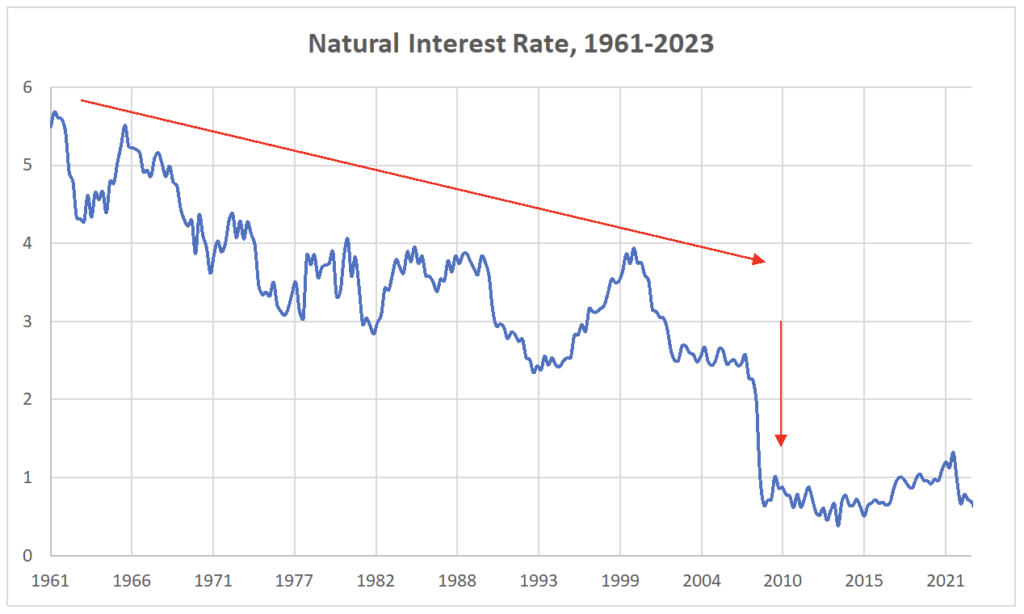

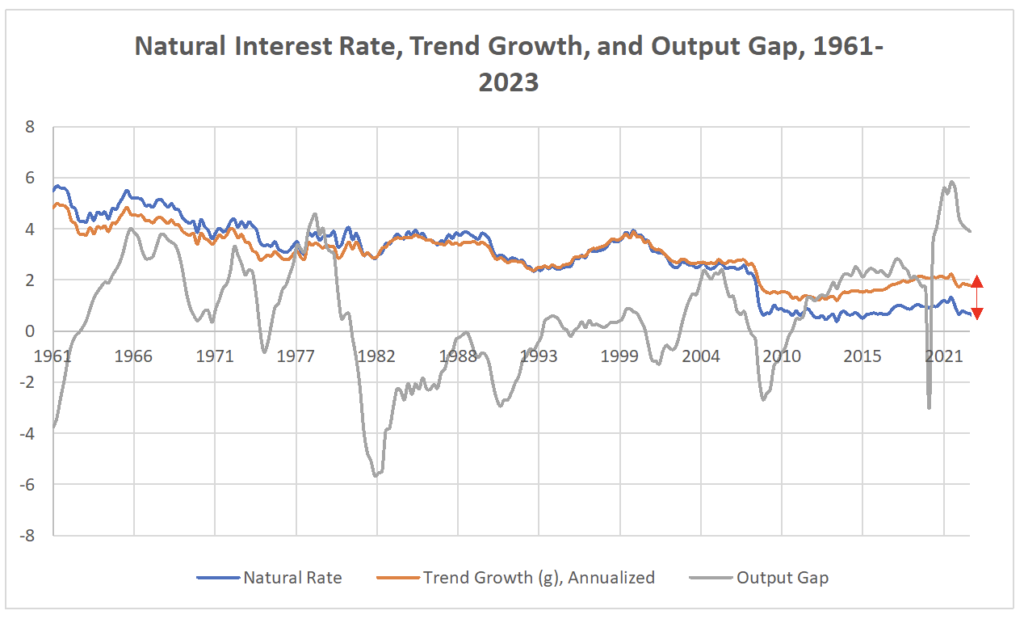

Chart 1 shows the estimated Natural Interest rate between 1961 and 2023, using one of the two models maintained by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The data shows a persistent downward trend throughout the period, with a sharp decline around the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008. As Chart 2 suggests, most of the pre-2008 decline can be attributed to a decline in the US trend growth resulting from demographic shifts and changes in investments made by businesses and governments. Some economists have suggested that increasing income inequality also played a significant role in falling rates as wealthy individuals save more money, thus increasing the supply of capital.2

Source: Estimates based on the model described in “Measuring the Natural rate of Interest after COVID-19,” by Kathryn Holston, Thomas Laubach, and John C. Williams, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 1063, June 2023. Data retrieved on September 11, 2023.

The decline in the natural interest rate around the 2008 GFC is of a much more sudden nature. Part of the decline can be attributed to the decline in trend growth, or what Larry Summers termed the Secular Stagnation fueled by changes in the economy from a manufacturing economy to a service-based one, an excess in savings, and demographic trends.3 But the growing space between the blue and orange lines in Chart 2 suggests another factor could be at play. One theory suggests that in the post-2008 world, investors are willing to accept a lower return on treasuries, the world’s safest and most liquid asset, and that this ‘convenience fee’ is driving interest rates down by up to 1%.4 Whatever the reason, the period between the GFC and the pandemic saw the natural rate sink to an unprecedented low before beginning a shallow climb around 2014. The climb came to a sudden halt in 2020.

Source: Estimates based on the model described in “Measuring the Natural rate of Interest after COVID-19,” by Kathryn Holston, Thomas Laubach, and John C. Williams, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 1063, June 2023. Data retrieved on September 11, 2023.

The Covid-19 pandemic, with its massive disruptions to the US economy, made estimating the natural interest rate in real time all but impossible. Lockdowns and extraordinary swings in GDP sent the Fed’s models into a spin, and the NY Fed stopped putting out estimates for several years. The model was relaunched in May of 2023 with measures designed to account for Covid-19 related policies as well as for the large economic shocks caused by the pandemic.5 The backfilled data suggested that the natural rate continued to climb until the end of 2021 before declining sharply in 2022, mirroring the shape of the stimulus-fueled economic recovery. When the stimulus came to an end, the natural rate appeared to sink back down to its mid-twenty-teens level.

Where are we Today

The NY Fed’s updated model puts the US’ real natural interest rate at 0.6%.6 If we add headline inflation of 3.2% or the 1-year expected inflation of 2.6%, we arrive at a nominal natural rate of 3.2-3.8%, suggesting that the Fed’s current funds rate of 5.25-5.5% is restrictive and should be slowing down the economy. But whether these rates are restrictive enough to curb sticky inflation, and especially core inflation that strips out food and energy, remains an open question.

But as the economy continues to show outstanding resilience in the face of steep interest rate hikes, a growing murmur can be heard from economists arguing that the natural rate may be trending higher, even if such a trend is not captured by the models. This is likely what Fed Chairman Jerome Powel hinted at in his speech in Jackson Hole when he cited the difficulties in estimating the natural rate.

Upward pressure on the natural rate could have multiple drivers. Demographic trends, namely, the retiring boomer generation, coupled with high levels of government debt coming out of the pandemic, could change the balance between supply and demand of capital, leading to higher rates. Others have suggested that trend growth could turn higher because of productivity changes due to artificial intelligence, onshoring, a tight labor market, and increased investments in areas like renewables and other green technologies. If this is true, it would mark a significant shift from the period of low growth that has plagued developed economies for the past decade.

But not all economists agree that growth and interest rate changes are shifting. As late as May of this year, John C. Williams, the president and CEO of the New York Fed argued that “Importantly, there is no evidence that the era of very low natural rates of interest has ended.”7

What Does This Mean for Investors

The debate about the path of the natural interest rate remains mostly a monetary policy question and offers few direct investment opportunities. Still, the Fed’s desire to make sure inflation is under control, together with questions about the natural rate, might drive the Fed to keep rates higher for longer. This uncertainty provides investors with both opportunities and risks.

On the opportunity side, higher rates open the door to introducing or increasing exposure to fixed income as an asset class. After almost 15 years of near-zero rates, investors can now put money to work in different types of bonds and at different durations to match their financial goals. Some might be tempted to stick with shorter dated treasuries, which are offering attractive yields topping 5%, until the uncertainty about the Fed’s future hikes is cleared up. This strategy entails significant reinvestment risk should the Fed over tighten and be forced to reduce rates. A preferred strategy might include buying into the bond market in tranches, known as dollar cost averaging, to further diversify their exposure to short-term developments.

On the risk side, higher rates could introduce volatility into the stock market, especially if the Fed defies expectations about future rate hikes. Higher rates are typically seen as bad for stocks, which now must compete with bonds while bearing a higher discount rate. However, strong economic growth could lead to higher earnings, which could in turn raise valuations. In all, uncertainty around rates means volatility in the stock market, and investors should be prepared to stay invested throughout.

Finally, the possibility of rates staying higher for longer should be considered seriously by borrowers of all types. Anyone counting on rates coming down anytime soon may be greatly disappointed. As my colleague Jeanette Garretty pointed out back in March, a bet that the Fed would cut rates sooner rather than later was likely a major contributor to the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank.

As we reach the likely end of the Fed tightening cycle, the question of what the new macro-economic status quo looks like will increasingly come into focus. There are good reasons to believe that interest rates could stay higher for longer, and investors should be prepared to seize the opportunities offered by higher rates while understanding the possible risks involved.

— AMD

Assistance in writing this article was provided by Chief Economist, Jeanette Garretty.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Source: Laubach, Thomas and Williams, John C., Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest (November 2001). Review of Economics and Statistics 85, no.4 (November): 1063-70.

[2] Source: Mian, Atif R. and Straub, Ludwig and Sufi, Amir, What Explains the Decline in r*? Rising Income Inequality Versus Demographic Shifts (September 22, 2021). University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper No. 2021-104.

[3] Source: Summers, Larry, U.S. Economic Prospects: Secular Stagnation, Hysteresis, and the Zero Lower Bound (2014), Business Economics, Vol. 49, No. 2

[4] Source: Del Negro, Marco and Giannone, Domenico and Giannoni, Marc P. and Tambalotti, Andrea, Safety, Liquidity, and the Natural Rate of Interest (May 12, 2017). FRB of NY Staff Report No. 812

[5] Source: https://www.newyorkfed.org/newsevents/speeches/2023/wil230519

[6] Source: Using the Holston-Laubach-Williams (2023) model, as of Q2 2023.

[7] Source: https://www.newyorkfed.org/newsevents/speeches/2023/wil230519

Disclosures

Investment advisory services offered through Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC (“Robertson Stephens”), an SEC-registered investment advisor. Registration does not imply any specific level of skill or training and does not constitute an endorsement of the firm by the Commission. This material is for general informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment, tax or legal advice. It does not constitute a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, has not been tailored to the needs of any specific investor, and should not provide the basis for any investment decision. Please consult with your Advisor prior to making any investment decisions. The information contained herein was compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but Robertson Stephens does not guarantee its accuracy or completeness. Information, views and opinions are current as of the date of this presentation, are based on the information available at the time, and are subject to change based on market and other conditions. Robertson Stephens assumes no duty to update this information. Unless otherwise noted, any individual opinions presented are those of the author and not necessarily those of Robertson Stephens. Performance may be compared to several indices. Indices are unmanaged and reflect the reinvestment of all income or dividends but do not reflect the deduction of any fees or expenses which would reduce returns. A complete list of Robertson Stephens Investment Office recommendations over the previous 12 months is available upon request. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Forward-looking performance objectives, targets or estimates are not guaranteed and may not be achieved. Investing entails risks, including possible loss of principal. Alternative investments are speculative and involve substantial risks including significant loss of principal, high illiquidity, long time horizons, uneven growth rates, high fees, onerous tax consequences, limited transparency and limited regulation. Alternative investments are not suitable for all investors and are only available to qualified investors. Please refer to the private placement memorandum for a complete listing and description of terms and risks. This material is an investment advisory publication intended for investment advisory clients and prospective clients only. Robertson Stephens only transacts business in states in which it is properly registered or is excluded or exempted from registration. A copy of Robertson Stephens’ current written disclosure brochure filed with the SEC which discusses, among other things, Robertson Stephens’ business practices, services and fees, is available through the SEC’s website at: www.adviserinfo.sec.gov. © 2023 Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC. All rights reserved. Robertson Stephens is a registered trademark of Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC in the United States and elsewhere.