April 2, 2024

By Jeanette Garretty, Chief Economist

Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.

–Paul Krugman, The Age of Diminishing Expectations (1994)

Every five or six years, certainly irregularly and usually prompted by some crisis of confidence in economic growth, company earnings or global competitive stature, US investors enter into a state that can be described as “productivity dysphoria.” Common manifestations of this mental condition include handwringing over the apparent lack of a game-changer technology on the horizon, long articles discussing the educational failures of the American labor force, and mind-numbing volumes of statistics offering international comparisons of investment in R&D. As is often the case after long illness, the rebound into recovery can be overly exuberant, resulting in a productivity mania that sees astounding opportunities for rising productivity everywhere in the economy.

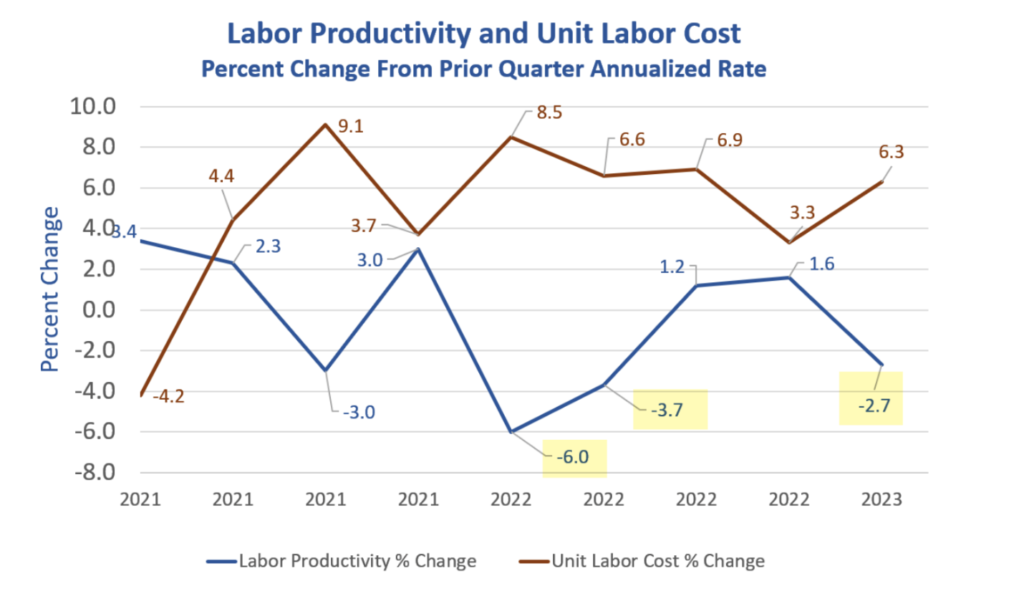

The essential truth in this phenomenon is that productivity, and, especially, productivity growth, is a critical and too often overlooked factor determining the health of the economy and the success of economic policy. A multitude of densely written economic papers can be easily found to explain what are relatively simple, intuitive concepts of considerable importance: 1) The rate of labor force growth plus the rate of productivity growth equals the long-run sustainable growth rate of the economy and 2) wage growth that is exceeded by productivity growth is disinflationary. Failing to appreciate the power of productivity has led to some vaguely amusing challenges for bankers and investors. During the rise of the semiconductor industry in Silicon Valley in the 1970s and 1980s, many wondered how an industry employing relatively highly compensated engineers located in a high-cost geographic area and producing a product which fell in price over time could make any money whatsoever. Therein lies a painful tale, for some, of an opportunity missed.

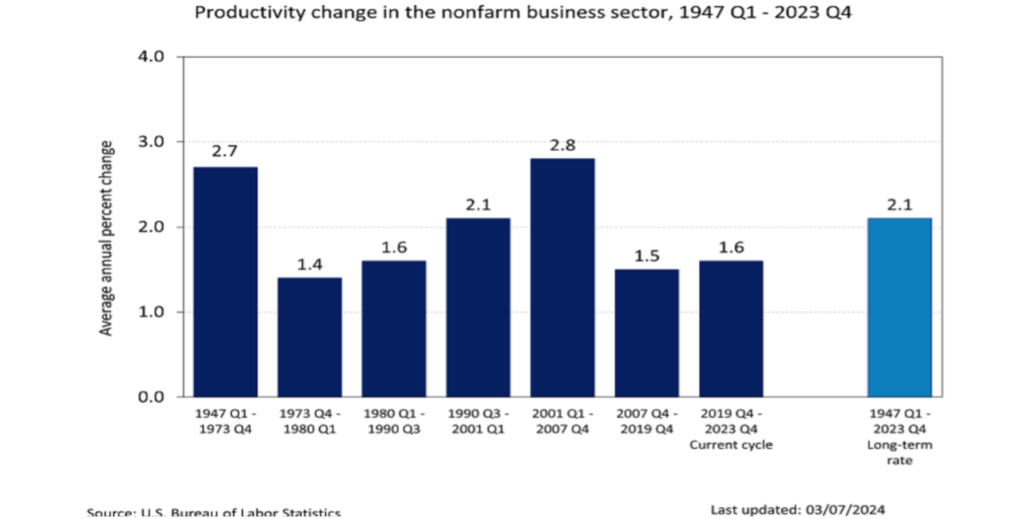

Between 1992 and 2000, US economic growth averaged an astounding 4%+. This was wildly above the Bureau of Census forecasts prepared in the 1980s, which contained dismal projections for both labor force growth (invalidated by a significant increase in immigration) and productivity growth. The decade was also notable for unemployment rates that fell below the magic 6% noninflationary unemployment rate number often cited by economists using the Philips Curve construct. Inflation, though higher than today’s 2% inflation target, declined across that same time period of the 1990s and mostly remained below 3%. It should perhaps be no surprise that by the end of the decade, then-Chairman of the Federal Reserve Alan Greenspan had ditched his irrational exuberance commentary of 1996 and become a true believer in the power of productivity growth (A Brave New Economic World? The Productivity Puzzle, paper by Kevin L. Kliesen, St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, January 1998) even though he really could not measure it and certainly could not forecast it. And in this is the root of the problem, as that same Alan Greenspan discovered when blamed for a monetary policy that failed to curtail the irrational exuberance that did eventually manifest itself.

A Critical Concept Without Clear Measurement

Trying to capture the reality of what is popularly thought of as productivity is full of bedeviling surprises. First of all, the productivity growth that must be paired with labor force growth to generate economic growth that will raise the standard of living, is total factor productivity (TFP) growth. One might raise the inherent productivity of the labor force through education and training, but if that labor force is not given the correct tools – if the capital stock is outmoded or energy inefficient or subject to errors and breakdowns—then the productivity growth contribution of the labor force will be compromised. Alternatively, if one pairs leading-edge technology with a labor force without adequate training, or if the application of that technology disrupts existing processes that have been implemented for efficiency of operation, the productivity improvement will almost certainly not be what one expects, at least initially. Indeed, this issue of the time required to actually experience true productivity gains from any change in labor or capital characteristics is one of the thorniest confronting economic policymakers. With large numbers of experienced workers choosing to retire during the COVID years, should the Federal Reserve expect a drop in productivity growth, making the fight against inflation harder, and when might they see that? Or, alternatively, will a labor force with a larger proportion of younger workers yield productivity gains due to a higher aptitude for technology and greater workplace mobility—and when might that happen?

Even more problematic is the question of what, exactly, is being measured. One suspects that, without realizing it, many people are still thinking in terms of widgets on an assembly line; widgets that can be easily observed and produced by labor that can be equally easily observed. Of course, this image does not fit well with the service economy that is the United States and may not even fit the modern assembly line that measures its success in terms of quality, not quantity (all references to Boeing will be passed down the line for someone else, with a stronger stomach, to address.)

Improvements in the quality of a widget or a service should be counted as contributing to a productivity increase, but the direct measurement of such improvements is highly imprecise, if not outright absent. The challenges become all the more daunting when one realizes that in the focus on economic growth and/or the mitigation of inflation it is not sufficient to simply have high productivity; productivity growth is the relevant metric, and it must occur year after year.

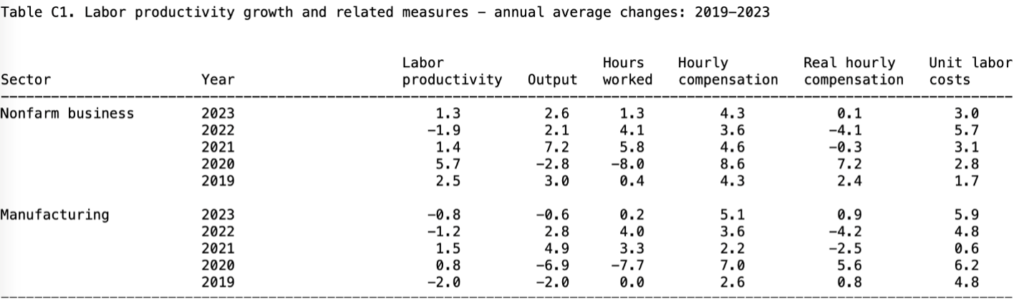

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reports on labor productivity quarterly and in some detail, which seems like something that should be useful to investors, economists and the Federal Reserve. The table below is a typical BLS report and well-illustrates the interplay between output, labor costs and productivity.

However, the labor productivity number is actually a residual figure, the end result of dividing a national output that may be impacted by any number of exogenous forces by the estimated hours worked by labor, and examining the difference over time. If, in a given quarter, GDP rises and hours worked remain unchanged, then it is determined that productivity rose. By the same accounting, if GDP falls and hours worked remain unchanged, then the labor force is now less productive. In neither of these examples is there a direct measure of the productive capacity of that labor force or the technology employed, which is really what inquiring minds and anxious investors and Fed officials want to know. Everyone would like to forecast productivity growth with some reasonable accuracy, but, to tell the truth, no one can even get the directional arrow correct most of the time.

Hindsight is Wonderful

Hindsight is not only the best way to understand productivity growth. It is the only way to understand productivity growth. Not simply through the analysis of macroeconomic growth trends that can only be explained by giving deference to the impact of productivity but also through microeconomic examination of industry- and job-specific developments that are well-documented over time. The view backwards is also perhaps the only way to appreciate how the productivity improvements associated with new technologies can sometimes end up in quite unexpected places, especially given that the biggest productivity growth is usually obtained when an industry has exhausted the technology’s capability to do something faster and has moved into the realm of innovating how to do something different.

Most casual observers are probably okay with this retrospective appreciation of how an economy benefits from productivity growth. Nor is hindsight simply a nice historical exercise; the examination of the past can and should be properly shaped into providing reasonable parameters for estimating the future. However, it is admittedly easy to be reminded of an old, hoary joke about three professionals stranded on a desert island with only a can of soup to eat and no can opener. The physicist suggests putting the can in the sun until the contents heat up enough to burst the can. The engineer considers a trajectory for throwing a rock at a coconut that will fall on the can and crack it open (added advantage: eat the coconut). The economist advises that the problem is solved by assuming a can opener. It seems ludicrous to proceed as if productivity changes do not occur when new technologies emerge or educational shifts materialize simply because that productivity change cannot be directly measured and forecast. Therefore, one is inclined to make certain assumptions about these critical changes and their impact, assumptions that may play out in the near, medium or longer term. Or then again, they may not. The only sure thing is that there will be surprises, some pleasant, some not.

The problem is that none of this uncertainty falls into the comfort zone of a monetary policymaker under pressure to identify the trajectory for economic growth, wages, and inflation and set interest rates accordingly. Even when productivity growth is the factor that will either make everything work according to forecast – think lower inflation while the economy roars ahead – or blow up the most carefully laid out theoretically sound plans, the number simply cannot be estimated, teased out, or nailed-down. The Federal Reserve may be data-driven, but the one piece of data they want, they cannot get.

Disclosures

Investment advisory services offered through Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC (“Robertson Stephens”), an SEC-registered investment advisor. Registration does not imply any specific level of skill or training and does not constitute an endorsement of the firm by the Commission. This material is for general informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment, tax or legal advice. It does not constitute a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, has not been tailored to the needs of any specific investor, and should not provide the basis for any investment decision. Please consult with your Advisor prior to making any Investment decisions. The information contained herein was carefully compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but Robertson Stephens cannot guarantee its accuracy or completeness. Information, views and opinions are current as of the date of this presentation, are based on the information available at the time, and are subject to change based on market and other conditions. Robertson Stephens assumes no duty to update this information. Unless otherwise noted, any individual opinions presented are those of the author and not necessarily those of Robertson Stephens. Indices are unmanaged and reflect the reinvestment of all income or dividends but do not reflect the deduction of any fees or expenses which would reduce returns. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Forward-looking performance targets or estimates are not guaranteed and may not be achieved. Investing entails risks, including possible loss of principal. Alternative investments are only available to qualified investors and are not suitable for all investors. Alternative investments include risks such as illiquidity, long time horizons, reduced transparency, and significant loss of principal. This material is an investment advisory publication intended for investment advisory clients and prospective clients only. Robertson Stephens only transacts business in states in which it is properly registered or is excluded or exempted from registration. A copy of Robertson Stephens’ current written disclosure brochure filed with the SEC which discusses, among other things, Robertson Stephens’ business practices, services and fees, is available through the SEC’s website at: www.adviserinfo.sec.gov. © 2024 Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC. All rights reserved. Robertson Stephens is a registered trademark of Robertson Stephens Wealth Management, LLC in the United States and elsewhere.