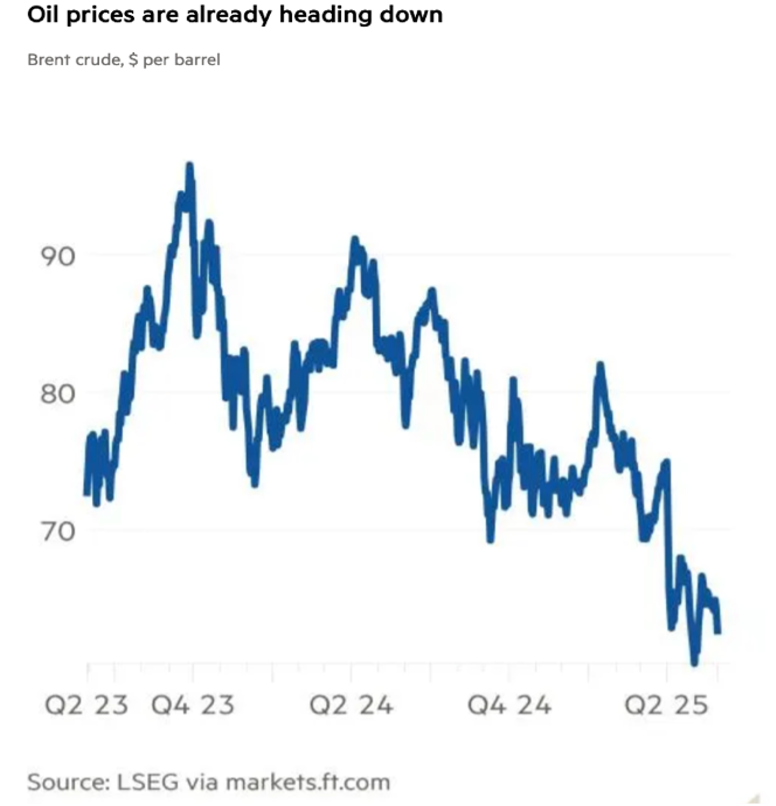

Oil prices have been falling as OPEC+ raises production quotas and weak demand growth fails to absorb the new supply. Yet, on June 2, OPEC+ agreed to increase production for the third consecutive month and signaled an intention to fully unwind the 5 million barrels per day (mmbd) in production cuts that had been undertaken in 2022 and 2023. Currently, OPEC+ states represent approximately 40% of the global oil supply and produce 41 mmbd. What’s the real story here? Explanations range from attempts to push non-OPEC+ producers out (US Shale Oil Producers are thought to need a $65/barrel price to be profitable) to reaping the benefits of keeping President Trump happy. The risk of prices falling even more than intended is significant, as global growth and manufacturing activity slow.

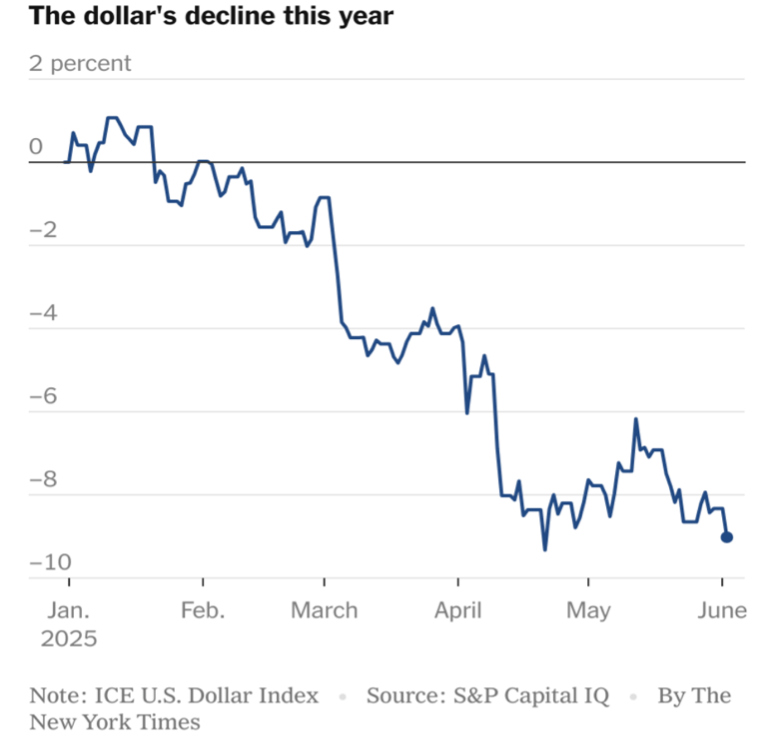

A precipitous decline in the US Dollar isn’t making life any easier for the budgets of OPEC+ countries receiving oil payments in dollars and needing to fund expenditures in a number of other currencies. In fact, the fall of the dollar this year is complicating life for many: US travelers abroad, US importers already contending with tariff-induced higher costs for imported goods, and foreign buyers of US Treasuries receiving suddenly much less attractive dollar returns. It is estimated that a Japanese bank buying US 10-year Treasuries and hedging the currency risk (as prudently demanded by risk management) would currently receive a yield of less than 1.5%, well below the yield on an equivalent domestic bond.

If you knew OBBBA like I know OBBBA . . .

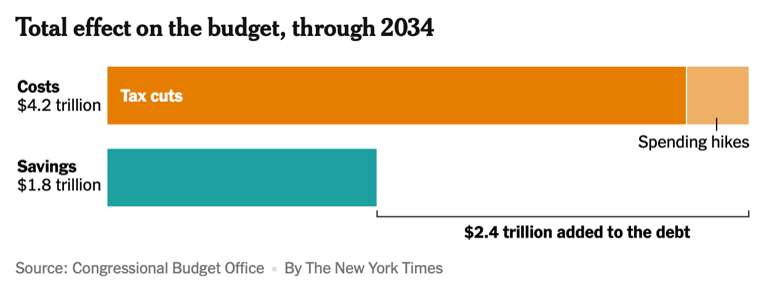

Mounting global bond market concerns over the long-term fiscal impact of the proposed “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” cutely nicknamed “OBBBA”, have contributed to the woes of the US Dollar. It should be remembered that the Trump 2017 tax cuts were passed with a provision to end in 2026 to make the budget numbers work. It was well understood at that time– and much discussed by non-partisan analysts such as the Congressional Budget Office and the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget — that the impact on the US debt position was scary enough that it needed to be mitigated with a 2026 sunset provision. OBBBA does away with that sunset and adds a few more tax cuts for good measure. Once again, the hope is that future economic growth will accelerate enough to reduce budget deficits through increased tax revenues. This hope has not proved to be a winning strategy in the 21st Century.

A decline in the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) Purchasing Managers Index for May is contributing to the debate over the near-term economic growth outlook. When the Index falls below 50, it signals contraction in the sector. While the ISM data also indicates that the manufacturing sector is contracting, the service sector number was surprising and somewhat worrisome, given the relative strength and resilience of the sector over the last year. Service industry purchasing managers cited tariff uncertainty as the major business problem, complicating attempts to forecast business and plan orders.

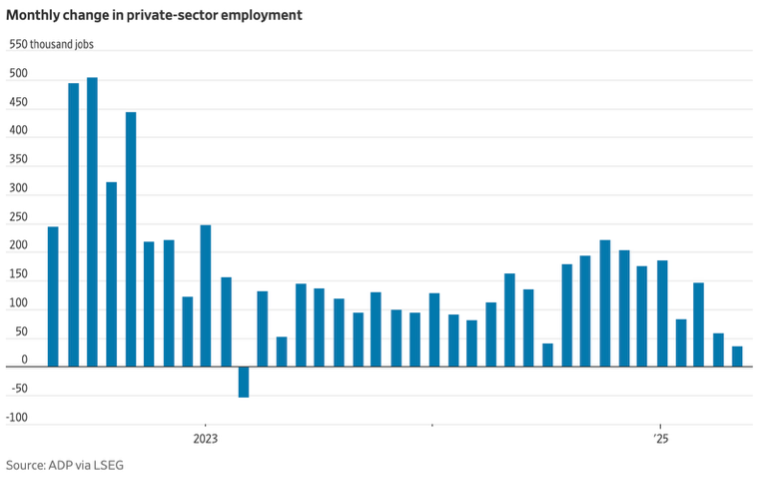

Amidst many signs that US economic growth is weakening, nothing commands as much attention at this critical moment as employment. ADP data is generally consistent with the more widely cited data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), but with concerns over staff cuts at the BLS and associated compromises in data collection and computation, the ADP figures have taken on heightened importance. For May, ADP reported that private sector hiring rose by a net 37,000, the slowest pace in two years. Nonfarm payrolls, as reported by the BLS for May, grew by 139,000, and the unemployment rate remained unchanged at 4.2%, but payrolls for the previous two months were revised downwards by a significant 95,000 jobs. These BLS numbers for May are likely to be revised downwards as well, especially given the job growth reported in the health care and travel/leisure industries, since data collection is notably “erratic.” One surprise in the BLS data was an 8,000 net job decline; analysts had expected an increase.