June 13, 2025 – In the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, many watched the unfolding European debt crisis with a mix of concern, curiosity, and self-satisfaction. Starting in 2009, Portugal, Ireland, Greece, and Spain (the so-called PIGS), among others, struggled to pay off their sovereign debt and were forced to accept international bailouts. These came with strict austerity measures that, in turn, drove public protests, political turmoil, and prolonged economic pain. Beyond schadenfreude, the crisis validated a tidy moral narrative that cast Southern Europeans as lazy and dependent on government handouts—as opposed to the hardworking and handout-free citizens of countries like Germany and the U.S.

Fast forward sixteen years, and the U.S. stands at its own fiscal crossroads. As the Big Beautiful Bill winds its way through the Senate, it appears increasingly unlikely to seriously address the U.S. deficit. This has reopened the debate about our long-term fiscal stability and prompted growing concern from both prominent voices and markets.

While the U.S. is not Greece, and today is not 2009, there are echoes worth paying attention to. History doesn’t repeat, but it often rhymes—and some of the choices Europe faced then may preview what we could face if we continue to do nothing.

Here are a few parallels worth considering:

1. The Limits of Sovereignty

Before the financial crisis, European governments enjoyed nearly unfettered access to capital markets. Investors largely treated Greek and German debt as interchangeable—until the illusion broke. Once doubt crept in, borrowing costs soared, and some countries found themselves shut out of the bond markets almost overnight.

The U.S. has long benefited from its role as the world’s safest borrower, backed by the dollar’s reserve status. However, as Liz Truss, the U.K.’s shortest-serving prime minister, found out in 2022 when markets revolted over unfunded tax cuts and borrowing costs spiked, confidence can evaporate quickly, even in mature, stable economies. The recent spike in U.S. long-term borrowing rates is a reminder that even the world’s largest economy cannot afford to ignore those it relies on to buy its debt.

2. Not All Debt Is Created Equal

Many economists believe that debt-financed spending can be a useful tool in economic downturns. However, several European countries entered the 2008 crisis already carrying high debt loads, with little room to maneuver. What once looked manageable quickly became destabilizing. Instead of spending their way out of a recession, these governments were left managing the debt they had accumulated in times of economic growth.

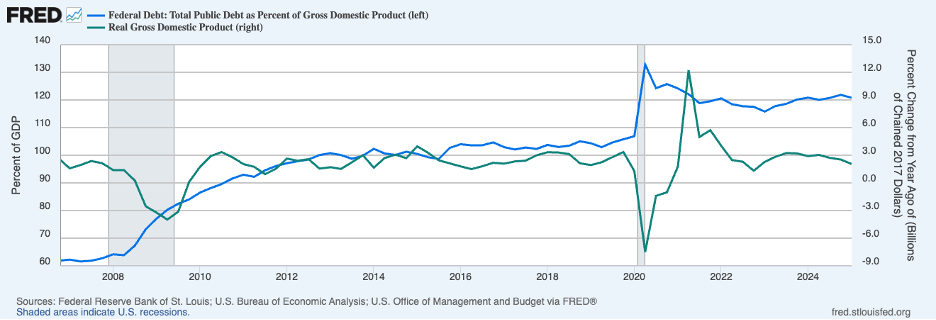

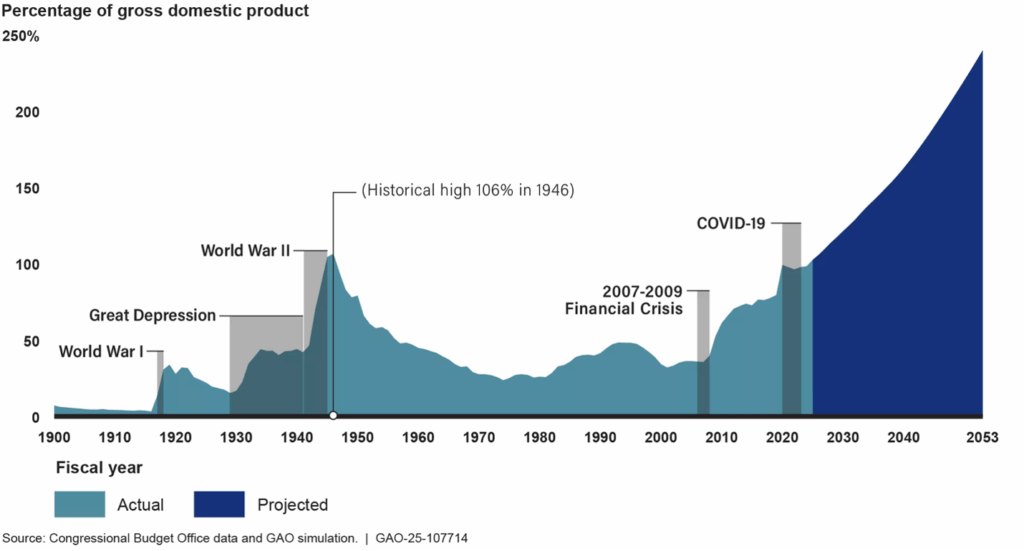

The U.S. has seen a similar pattern. Even during periods of expansion, our debt load has grown—driven by a mix of tax cuts, entitlement expansion, and bipartisan reluctance to reduce spending. Our deficit has become structural, meaning it persists even in good times, and this could pose a significant challenge in the next downturn.

There’s no clear threshold at which markets decide a country’s debt load is too high. Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio has long exceeded 200% with little disruption, while Greece triggered a full-blown crisis below 185%. The takeaway isn’t that the U.S. is nearing a crisis, but that tipping points are based on perception—and that perception can change fast.

3. There Are Only Ugly Ways Out of a Debt Crisis

Once investors lost confidence, many European countries were forced into austerity: raising taxes, slashing spending, and trying to appease bond markets. In some cases, these measures restored balance sheets. But they also deepened recessions, weakened public services, and fueled political unrest. There were no clean outcomes, only difficult tradeoffs.

The best way out of a debt crisis is not to get into one. A good analogy is a family spending well beyond its means. It can choose to downsize voluntarily—selling the big house and trading in the luxury car—or wait until the bank does it for them, on worse terms. Similarly, waiting for a market crisis to force action almost guarantees a worse outcome. Once the music stops, there are only bad chairs left.

4. Polarization Complicates Both Prevention and Recovery

The European debt crisis wasn’t just economic; it was deeply political. Governments fell, coalitions collapsed, and trust in institutions eroded. Fiscal reform became nearly impossible in an environment where consensus couldn’t be found.

The U.S. is not immune to this dynamic. Hyper-polarization has made any serious attempt at deficit reduction inherently partisan. Debt ceiling standoffs, threatened shutdowns, and performative fiscal debates have made long-term planning nearly impossible. If markets lose confidence, the need to act swiftly and decisively could clash with a system that increasingly struggles to do either.

5. The Longer We Wait, the Harder It Gets

In Europe, aging populations increased pressure on public finances, adding a slow-burning fuse to an already volatile situation. The problem wasn’t just debt levels—it was that demographic trends made those debts harder to sustain over time.

The U.S. faces a similar arc. Social Security and Medicare are on trajectories widely seen as unsustainable. These challenges are predictable—and fixable—but only if addressed with foresight. Delaying reform doesn’t make it easier. We can tackle these issues during a period of relative stability, or we can be forced into doing so during a crisis. One of those paths is clearly better, but it requires political will we’ve yet to summon.

No one can say with certainty how the U.S. deficit story ends. The spending side is relatively well understood, driven by demographic shifts and long-standing commitments, but that doesn’t account for unexpected events like Covid or a global financial crisis. On the revenue side, stronger-than-expected economic growth could provide relief, though that would require solving for persistent labor shortages and stagnant productivity. New tariffs may bring in additional revenue, but they also risk slowing growth, potentially cancelling out the benefit.

In the absence of a crystal ball, history offers a useful guide. Countries that run persistent deficits are vulnerable to the whims of capital markets, markets that care little for a nation’s internal politics or social priorities. That moment of reckoning could come tomorrow, or it could come never. But at some point, the U.S.—like every household, company, or country—will have to make its income match its expenses.

— AMD