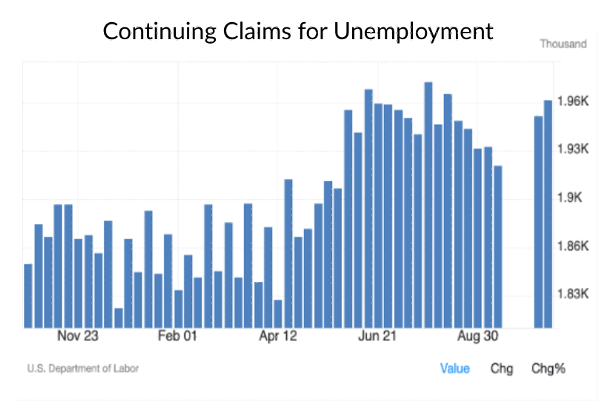

A good example of how the government shutdown has affected critical economic data is provided by the continuing jobless claims report released this week by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The data gap shown in this chart is possibly irretrievable, but there is an effort to quickly fill in at least some of the holes. In this case, the numbers for the weeks of October 11 and October 18 arrived at the same time, serving to illustrate the great concern over the weakening labor market. Private sector reports on economic conditions continue to be carefully reviewed, and the ADP weekly employment report showed employers cutting an average of 2,500 jobs per week over the last month.

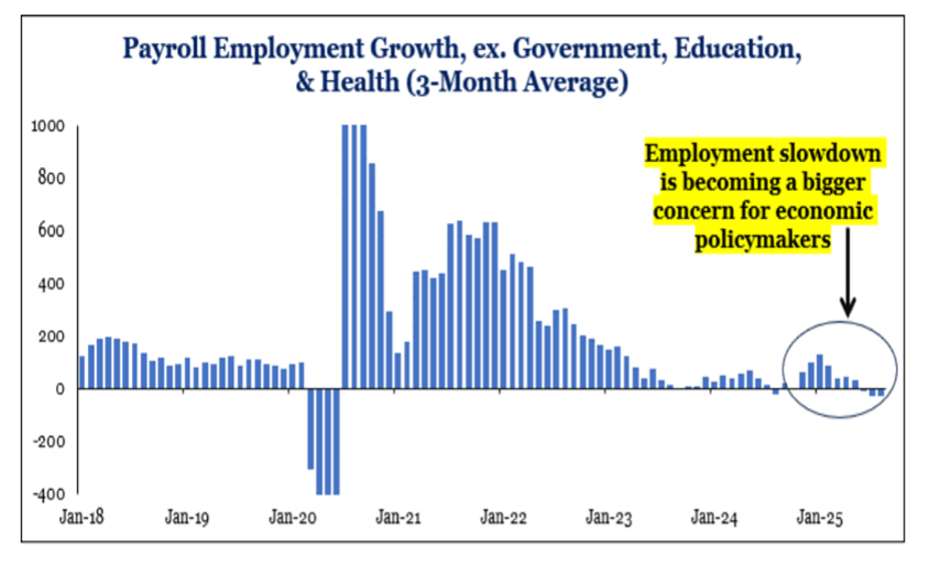

The much-delayed September employment report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics on Thursday, November 20, contained a surprising rise of 119,000 in non-farm payrolls— and a not-so-surprising downward revision in the job count for August and July. Given the abundance of evidence that employment growth has slowed, though maybe not fallen into negative territory, expectations are high that this September report will be revised downwards as well. It is worth keeping in mind that most of the September data was collected before the shutdown; October data was not (and may never be.)

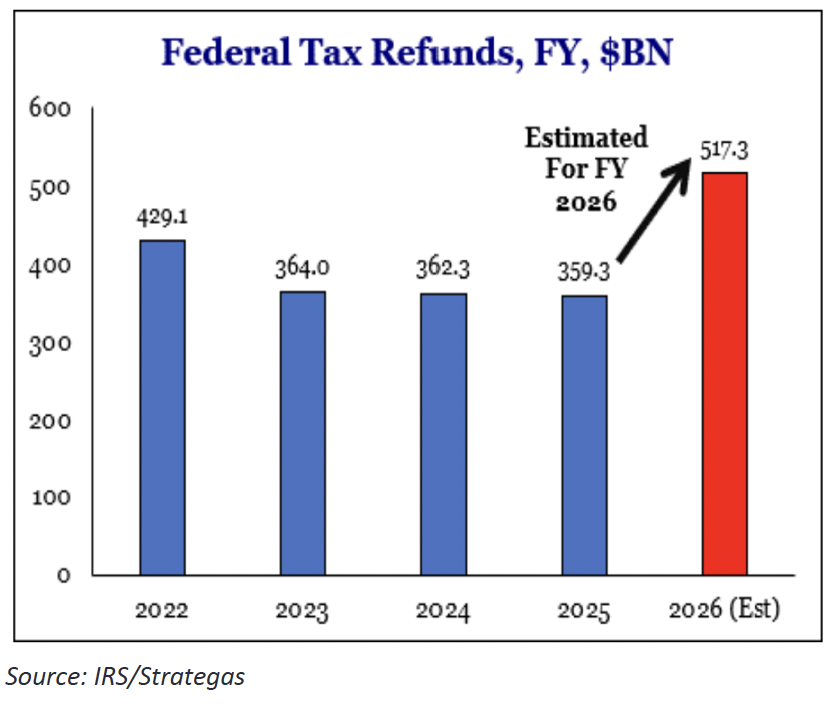

Consumers are thought to be increasingly pessimistic about the economy and worried about potential job loss in a difficult labor market. Consumer confidence has hit near-record lows in some surveys. However, policy makers and business leaders remain cautiously optimistic about the outlook for spending, emphasizing that income growth appears stable and that there will be a significant uptick in tax refunds starting early next year. This week’s Bureau of Labor Statistics report for September indicated that wage growth remains modest, but, at 3.8%, it is comfortably ahead of inflation.

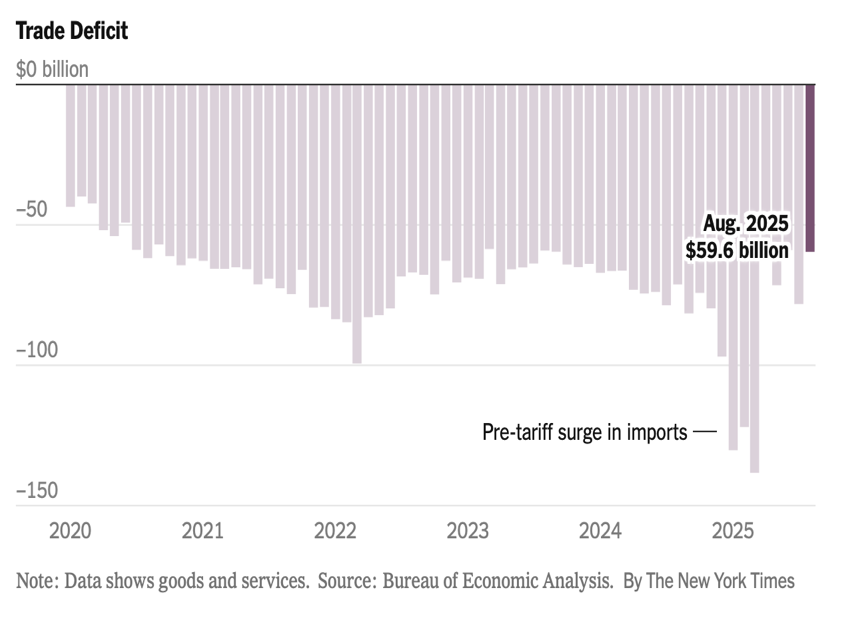

Another cause for optimism in the economic outlook is the falling trade deficit, one of the key White House policy objectives this year. Americans and American businesses have sharply cut back on imports in response to tariffs and to political pressure aimed at boosting domestic production and consumption. Theoretically, this means that more spending was directed to US production of goods and services, supporting employment gains and generating domestic income. However, in some cases, a drop in imports may simply reflect a loss of demand, especially in the short-term when domestic production may not have been able to ramp up. Overall, the trade deficit for 2025 is still above that of 2024.

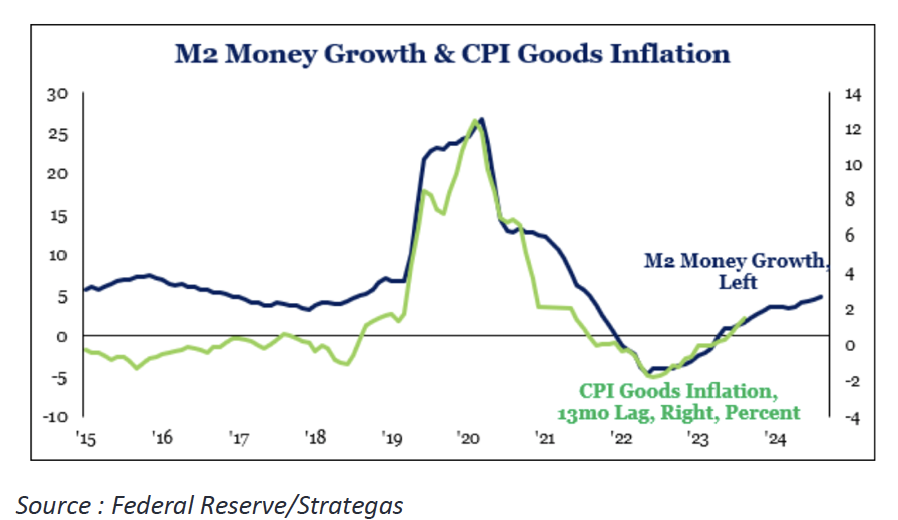

Many will not remember the definition of M2 Money Supply; it’s been a long time since anyone talked about the various measures of money supply. M2 is defined as currency, checking accounts, time deposits, short-term money market funds, and similar instruments. It is the most traditional concept of the money supply, and there is a substantial history of using M2 to understand Federal Reserve policy and its implications for inflation. With a long view, a relationship between M2 and inflation can provide useful insight. Over shorter time periods, the relationship is less helpful. Nevertheless, it is worth considering that M2 is not growing in such a way that implies an increase in inflation is likely. The Federal Reserve is expected to take this into consideration at its next Federal Open Market Committee meeting in December, at which it will once again debate the relative risks of rising inflation versus slowing employment.