By Avi Deutsch

November 25, 2025 – As we digest the results of November’s elections, a common narrative is emerging that ties the outcome to a stubborn reality: life still feels expensive. Cost of living dominated local debates and exit polls, echoing concerns that have lingered since the inflation peaks of 2022–2023. While headline inflation has cooled, the perception—and in many cases, the reality—of high prices remains. Rent, groceries, childcare, and transportation continue to strain household budgets, especially for those without the cushion of assets.

This isn’t just a story about prices. It’s also a story about distribution. The last five years have seen a tremendous increase in household wealth, but most of these gains accrued to the owners of assets, including stocks and real estate. As the Wall Street Journal summed it up earlier this month: “Feeling Great About the Economy? You Must Own Stocks.”

The K-Shaped Economy: Five Years Later

As many have noted, the pandemic’s economic shock created a split recovery. Asset owners—those with equities, real estate, and retirement accounts—benefited from surging markets and historically low rates. Others, especially renters and wage earners in service sectors, faced job volatility and rising costs.

The numbers tell the story:

- Household wealth grew by $67 trillion between early 2020 and Q2 of 2025. Of this growth, 63% (or $43 trillion) went to the top 10% of households.[1]

- Today, the wealthiest 10% account for nearly half of all U.S. consumer spending. This concentration means aggregate spending looks healthy even as millions of households cut back.[2]

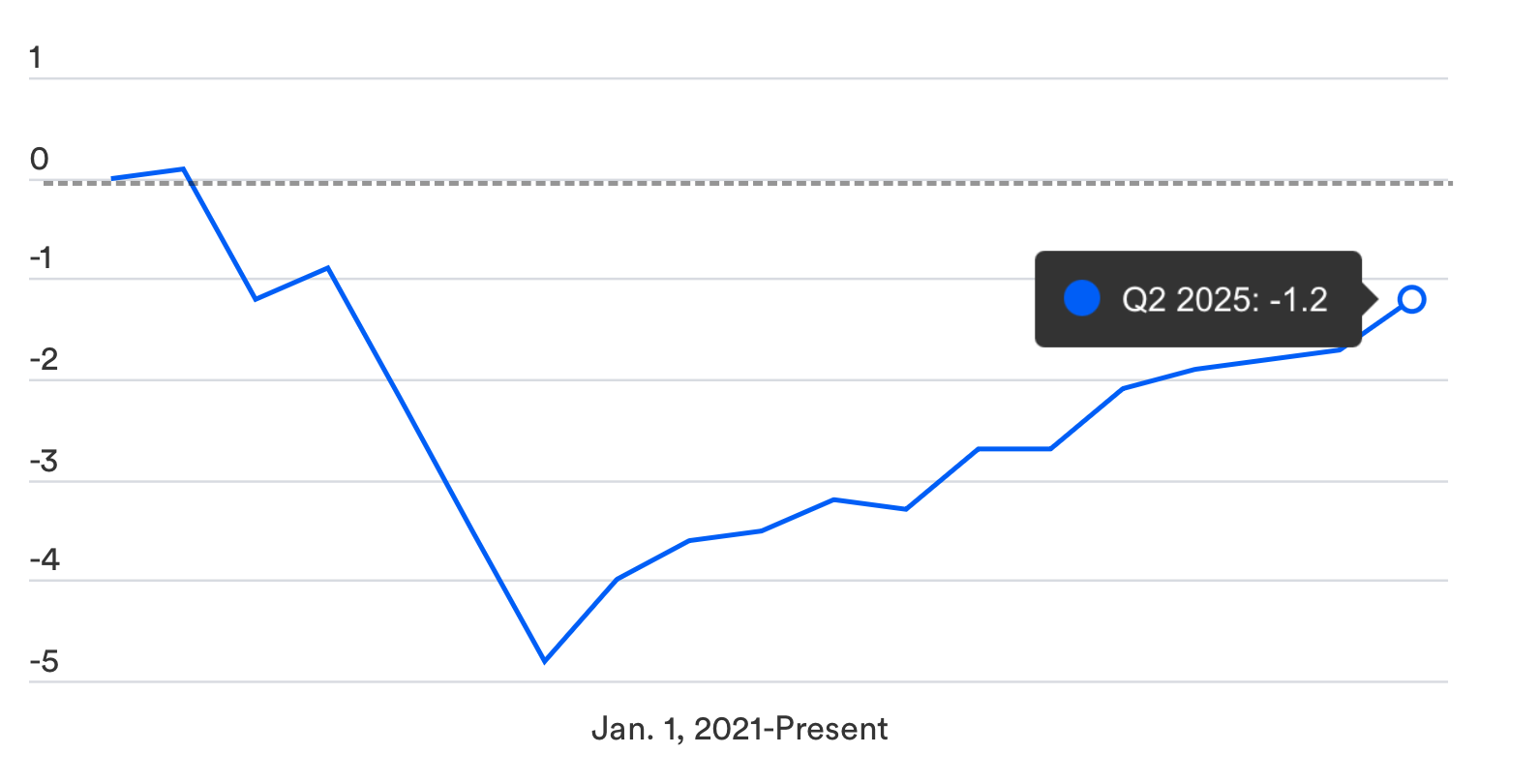

- On average, U.S. workers are earning less today, in real terms, than they did in January 2021.[3] This suggests that many employees—especially those without assets—have not benefited from much of the economic growth of the past four years.

As the U.S. economy continues to slow, this pattern of economic divergence could make the economic system less resilient. Delinquencies on mortgages, credit cards, auto loans, and student loans have all surpassed their pre-pandemic levels, suggesting that the slowdown is hitting less affluent borrowers hardest. [4] Recent corporate earnings calls point to the same divide: some consumers are struggling, while others are doing fine.

Enter AI: More Asset Growth, Less Jobs

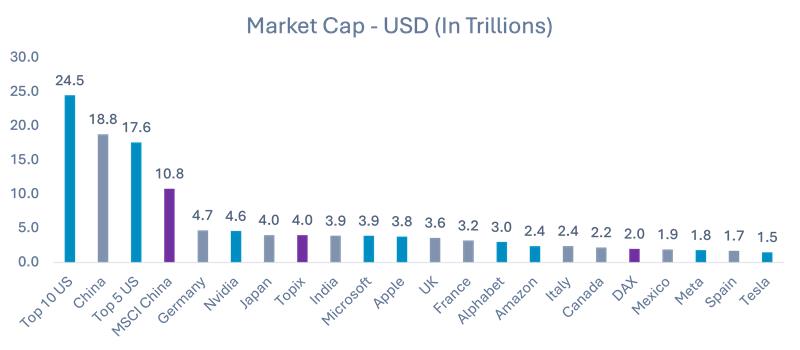

AI has become the defining economic narrative of 2025, and its impact on the cost of living and inequality is multifaceted. First and foremost, AI has fueled a surge in asset prices, further increasing the wealth of those holding stocks and other investments. The 10 largest U.S. companies in the S&P 500—widely viewed as the likely winners of the AI race—now make up 41% of the index by market cap and account for 33% of its earnings. [5]

To illustrate their scale: the 10 largest U.S. companies are collectively worth more today than the economic output of Germany, Japan, India, the U.K., France, Italy, and Canada combined.

Recent market corrections have dampened some of this year’s stellar returns, but only slightly. For many, the pullback felt expected after a sustained period of rising stock prices—and perhaps not significant enough. The deeper truth is that valuing companies today is unusually difficult because we have little idea what these businesses will look like in ten years. AI may be overhyped, or it may be underhyped. One thing appears certain: AI is going to change how businesses operate. It already is, which brings us to the labor market.

Alongside a generally slowing labor market, there are growing signs that AI is changing hiring practices, especially for entry-level roles. The data is still mostly anecdotal, but the pattern seems clear to many who have integrated AI tools into their daily workflow.

How AI will influence work in the longer term is a matter of much debate, but history suggests that with time businesses will find a good use for people’s skills in jobs that can’t (yet) be performed by AI, from eldercare to plumbers. But even if this is true, there will almost certainly be a generation that is too late to transition. An unfortunate casualty of tremendous innovation.

Reflecting on Change

Between 1811 and 1816, a group of English textile workers began destroying the newly created cotton and wool mills they believed threatened their jobs. They fashioned themselves as followers of a legendary (and likely fictional) Ned Ludd, who supposedly smashed two knitting machines in a fit of rage. They are known to history as the Luddites.

The Luddites didn’t resist technology because they feared change—as the term is often used today—but because the technology threatened their livelihoods. The real lesson is that technological innovation, which has driven the greatest improvements in human living standards, also disrupts lives as it emerges. The growth of AI, when combined with the sustained increase in cost of living over the past five years, may put our society in a fragile position. It is no coincidence that political movements in both parties are reorienting around the cost of living as the core national issue. Even those who have benefited most from today’s economy would be wise to take notice.

**

As we enter this Thanksgiving holiday, I hope to reflect on the opportunities I have been given, including the privilege of witnessing a period of breathtaking technological innovation. I hope also to remember that not everyone has enjoyed the same economic gains over the past four years, and not all will benefit equally from the AI revolution. This season invites us to reflect on how we wish to face these challenges as a society, and on the role each of us can play in shaping the world we want to see.

With gratitude and hope for a season of reflection, clarity, and connection.

— AMD