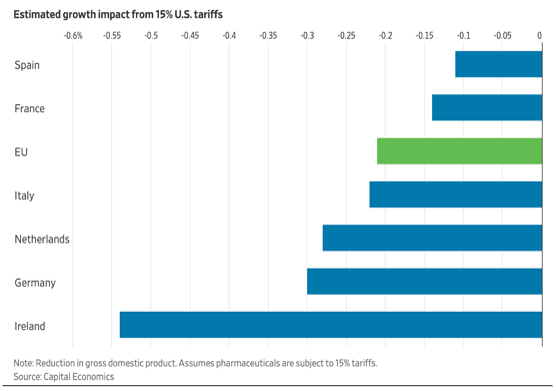

The European Union (EU) arrived at a tariff “deal” with the US comfortably before the August 7 deadline. The merits of doing that may be illustrated by the alternative, such as Switzerland’s 39% tariff. Nevertheless, the deal is not without consequences for the EU, reflected in new estimates of the impact on projected economic growth over the course of 2025 and 2026; in essence, the imposition of tariffs lowers the near-term trajectory for GDP, in various countries, differentially. Keep in mind that many details of the deal remain to be ironed out, and product/industry exceptions to the 15% tariff regime are likely (both positive and negative).

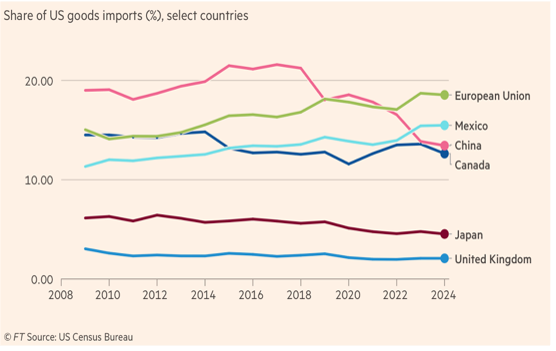

For US consumers and businesses, the EU is a very important trading partner. In terms of US imports, many would be surprised to see the EU’s role as much larger than China or Canada. US exports to Europe represent approximately 14% of European imports, second only to China. As a percentage of total US exports, exports to the EU are estimated at 15%, a figure that has been declining for many years as the US has diversified its export markets and as EU growth slowed. s population growth slows and medical care helps people live longer. Individual countries can alter their population growth outlook via immigration policies, but globally, the only effective action is an increased birth rate and increased life span. Very long-range projections are often surprisingly wrong; this one is worth watching and thinking.

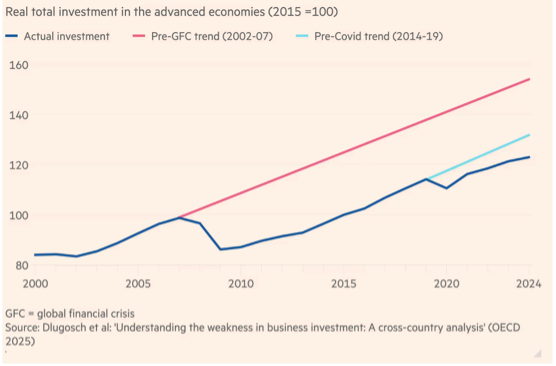

Many economists take a keen interest in the effect of tariffs and global trade wars on business investment spending. The advanced economies (aka “developed economies”) of the world are commonly experiencing a slowing of population growth, with worrisome implications for labor force growth. Raising the productivity growth rate of a more slowly growing labor force is of paramount policy importance and is viewed as being critically dependent upon investments in equipment and technology. Both the global financial crisis and the pandemic appear to have moved investment spending off the trajectory established in the early 2000s, despite very low interest rates for much of that period of time. (Note: business investment in digital technology has accelerated but is still outweighed by the deceleration in plant and equipment spending.) Tariff-associated uncertainty threatens to be an additional hit to the trendline, although one that may be mitigated by new technologies and supportive, targeted government policies.

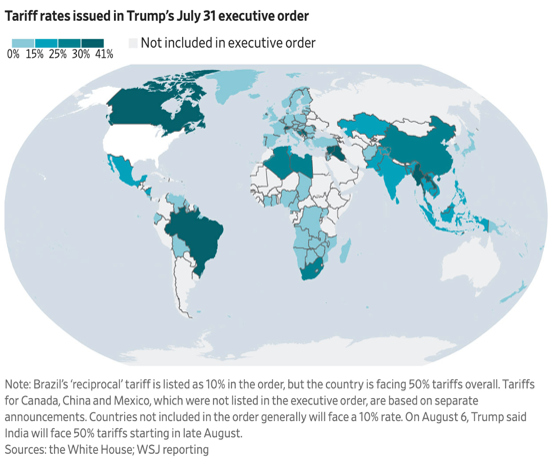

Most of the US tariff regime is now in place and in effect. Exceptions are expected, possibly even roll-backs. Numerous countries are now measuring “success” by evaluating how the US tariffs imposed on them compare with competitor countries, i.e. the relative advantage or disadvantage at which their exporters now find themselves. Companies are doing the same thing, attempting to determine an advantageous strategy for supply chains and production facilities. The more expensive the strategic re-direction, however, the less likely it will be soon undertaken; uncertainty remains high about the stability and durability of current tariffs, raising the risk of making expensive mistakes.

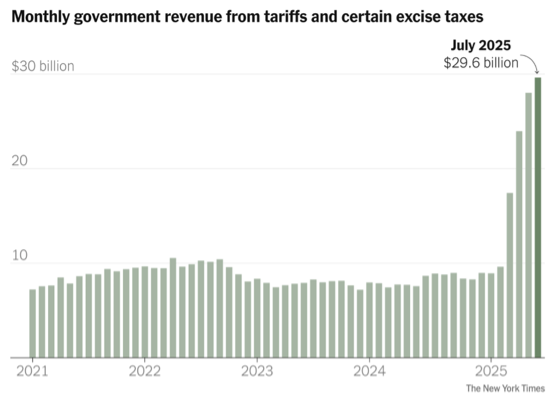

Even before the more widespread tariff impositions on August 7, the collected US tariff revenue had been steadily increasing. The magnitude of the shift of private sector monies to government coffers is stunning, prompting some discussion of returning a portion of the receipts to individuals and businesses. Deficit hawks in Congress have already weighed in on their intention to direct the windfall towards reducing budget deficits and the national debt; for the moment, their arguments have prevailed.